The question was one Michael Bourque ’89 expected, but hadn’t heard in some time. “Fresh mushrooms, or canned?” the waitress at Pat’s Pizza asked, evoking a chuckle during a recent visit to his old Orono stomping grounds.

“If I’m here, it has to be canned mushrooms,” Bourque said, sending the server on her way, smiling.

Some things, it seems, never change. And some things, Bourque will tell you, have changed so much, you can hardly believe them.

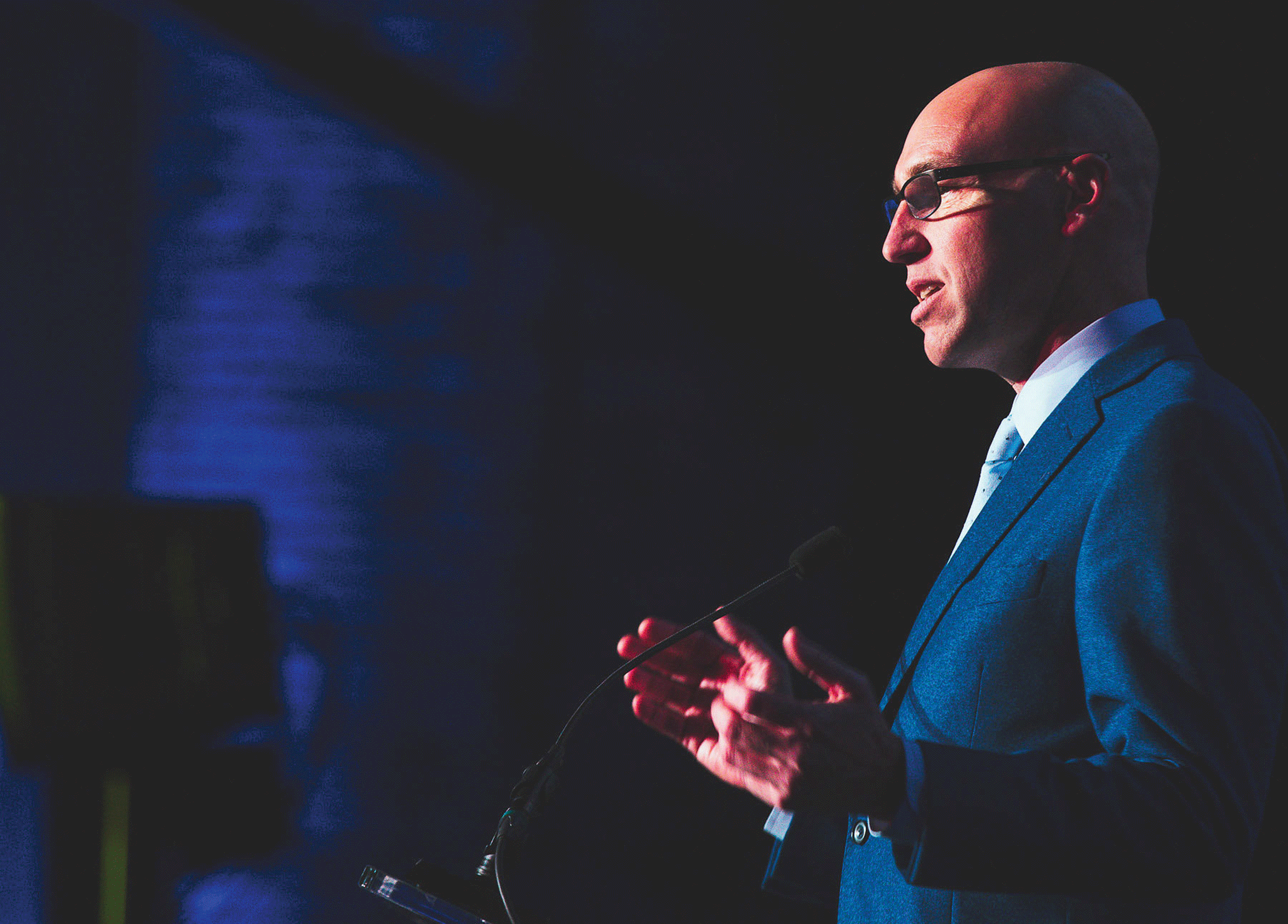

That’s why on this chilly night, the former award-winning sportswriter and sports editor of the then-Daily Maine Campus, Bourque sat in a booth, tinkering with a jukebox that no longer functions while he explained his career path—specifically, how he worked his way up through the ranks of Maine Employers’ Mutual Insurance Company (better known as MEMIC) to become its president and CEO.

“Nobody ever intends to go into insurance,” Bourque said. “It’s not like it’s a plan.”

Instead, Bourque’s intent was to be–come a sportswriter, and to use his knowledge of college hockey, which he honed during his time at UMaine, to gain a full-time writing gig at a daily newspaper.

During his senior year he was feeling adventurous, so he applied to two newspapers in Alaska, far removed from his native Maine. One newspaper turned him down, saying it sought a candidate with five years of experience. Then one day, as he sat in his room at Sigma Phi Epsilon, he fielded a call from a slow-talking transplanted Texan, the sports editor at the Anchorage Times.

“There was a delay, as [the signal] was bouncing off satellites. After every answer, there’d be a delay,” Bourque says. “I was like, ‘This is going terribly. I’m just bombing this interview … then he says, ‘I’m going to send you a plane ticket if you’ll commit to come.’ He sort of called my bluff.”

Bourque went. He spent just over a year there before ending that adventure and returning to Maine for another newspaper job.

Then, four years after his college graduation, he looked at the life he’d chosen and discovered something that changed everything.

“I realized that I didn’t see any old, happy reporters,” Bourque says. “So I asked, ‘I wonder what else I could do?’”

The answer, it turns out, was public relations. It didn’t take long before Bourque learned that the research and communications skills he had honed as a journalist for newspapers in Anchorage, Alaska, and Biddeford, Maine, might serve him well.

His first PR job was in Washington, D.C., with the American Association of Community Colleges. And when he and his future wife, Melissa, moved back to Maine in 1995, Melissa’s mother told him about a potential job opening at a new company with a funny name: MEMIC.

“I didn’t know a thing [about insurance],” Bourque says. “But what I’ve said all along, and what I continue to do, is, I learned the business along the way. And I always say, I kept my reporter’s license to ask dumb questions, and keep asking, and try to understand how somebody outside the company would understand inside, and kind of act as a translator.”

That approach paid off, he says, because it forced him to understand how to explain many different facets of MEMIC, and gave him a great working knowledge of the company. Promotions followed, and for 17 years he worked directly under founding CEO John Leonard.

And he often found himself thinking of a man he said was a casual public relations mentor from his college days.

“I think I’ve learned marketing, promotions, from [former UMaine hockey coach] Shawn Walsh, because I interviewed him after every game [I covered for the campus paper] and there was nobody better at promotions and PR than he,” Bourque says. “It was an informal education, but certainly valuable in my PR, marketing world … he was always positive, even after a tough night.”

Another person he thinks of often: Bob Steele, a journalism ethics professor he studied under at UMaine.

“The ethics [coursework] is stuff that translated throughout life and business. It just does,” Bourque says. “That experience was a lasting one.”

MEMIC had about 150 employees when Bourque started, and was only two years old. Today the workers’ compensation company employs 410 people, has $1.3 billion in assets, and made $371 million in revenue last year, according to Bourque. The company does business across the country, but most of it still takes place in Maine and along the East Coast.

Not that Bourque’s advancement, nor his life, has been without difficult times.

In 2014, his wife, Melissa, passed away after a three-year battle with cancer. That loss left Bourque without the love of his life, and his 14-year-old twins, William and Kathryn, without their mom.

That’s when he began to more fully recognize the magic around him.

“Nobody would want to be going through this, but you react to the things that happen, and hopefully you’re true to yourself,” Bourque says. Everywhere he looked — at church, in the civic organizations he had joined, at MEMIC — he found people who wanted to help him and his children.

“We had tremendous support from our community,” he says. “So that was a big deal.”

Today, Bourque’s children are 17, and juniors in high school. They’re looking at colleges now, and he hopes they consider UMaine.

Without UMaine, he points out, there would be no Michael Bourque.

And that’s not mere hyperbole.

“One of the things that made UMaine special to me is that my parents (Peter ’64 and Mary Thomas Bourque ’65) met here, so I would not exist if not for the University of Maine,” he says. ”Their first date was [for] a coffee in the Bear’s Den.”

So what’s next for Bourque and MEMIC?

The first answer first: “We could keep growing, growing, growing. We’ve grown quickly, but the goal is not to be the biggest, but to be the best [workers’] comp company in America,” he says. “We’re excited to be able to bring to these other states what we’ve brought to Maine.”

And personally, he wants to keep running around Back Cove in Portland and to go fishing, a family passion. Bourque also has a girlfriend with whom he enjoys spending time.

“But in the meantime, I’m making sure my 17-year-olds are on a good path,” he says.

And after the one he has followed, Bourque ought to know what a good path looks like.