Published June 20, 2017

A proposed 113,000-square-foot Engineering Education and Design Center will move UMaine Engineering into modernity — and Maine into a new economy.

By Clinton Colmenares

If you build it… well, you know the rest. Everyone knows the rest. An all-world team wants to play, but they need someone, anyone, to carve out a cornfield.

But what if there aren’t enough people to build it, whatever it is—buildings, roads, bridges, airplanes, technology? How will they come? Or, rather, where will they go? In Maine, engineers—the people who design and oversee the building of nearly everything, whether it’s made of steel or silicon—are increasingly scarce, and the space to educate new engineers at UMaine is maxed out.

Dr. Dana Humphrey (left ), dean of the College of Engineering at the University of Maine, rattles off engineering education and workforce statistics like some people report their favorite team’s batting averages or pitcher production.

), dean of the College of Engineering at the University of Maine, rattles off engineering education and workforce statistics like some people report their favorite team’s batting averages or pitcher production.

Half of Maine’s high school students who want to become engineers go out of state for college.

• 27 percent of engineers in Maine are 55 and older. (When they retire, “that’s a quarter of the engineering workforce; poof, it’s gone!” he says.)

• Four of the college’s 11 programs are enrollment capped. (“There are more students than we have room for.”)

• Including the District of Columbia, Maine ranks 51st in per capita production of engineers with master’s degrees.

• If the youngest engineering education building in Orono were a person, it would be just four years away from getting its AARP membership card.

Humphrey has spent his entire career at UMaine. Like any great leader, he loves the team, he’s invested in its success, and he has a three-step plan to right the ship. The first step, addressing critical safety and maintenance issues, is complete. The last step is to overhaul the existing buildings that have been around for half a century or more.

The second step is the crown jewel: the Engineering Education and Design Center, an $80 million, 113,000 square-foot facility necessary to attract the builders and designers of the future—not only for the university, but also for the state of Maine.

UMaine President Susan J. Hunter says the construction of such a facility is essential to the university’s ability to fulfill its mission. University of Maine System Chancellor James Page shares that sentiment; in a January 12 meeting with the UMaine Alumni Association Board of Directors, he said the Engineering Education and Design Center is the System’s number one capital construction priority.

To understand the need and the benefits of the project, one needs to understand engineering education in a 21st century context.

Engineering a new learning environment

The days of sitting in class, listening to lectures, and doing homework alone late at night in a library carrel havegone the way of blackboards and spiral notebooks. Education, from K-12 through doctoral levels, now often takes place in a “flipped-classroom” environment: students “pre-learn” course material on their own time. When they come to class, they plug in and work together on projects in small groups under the watchful eye of the professor.

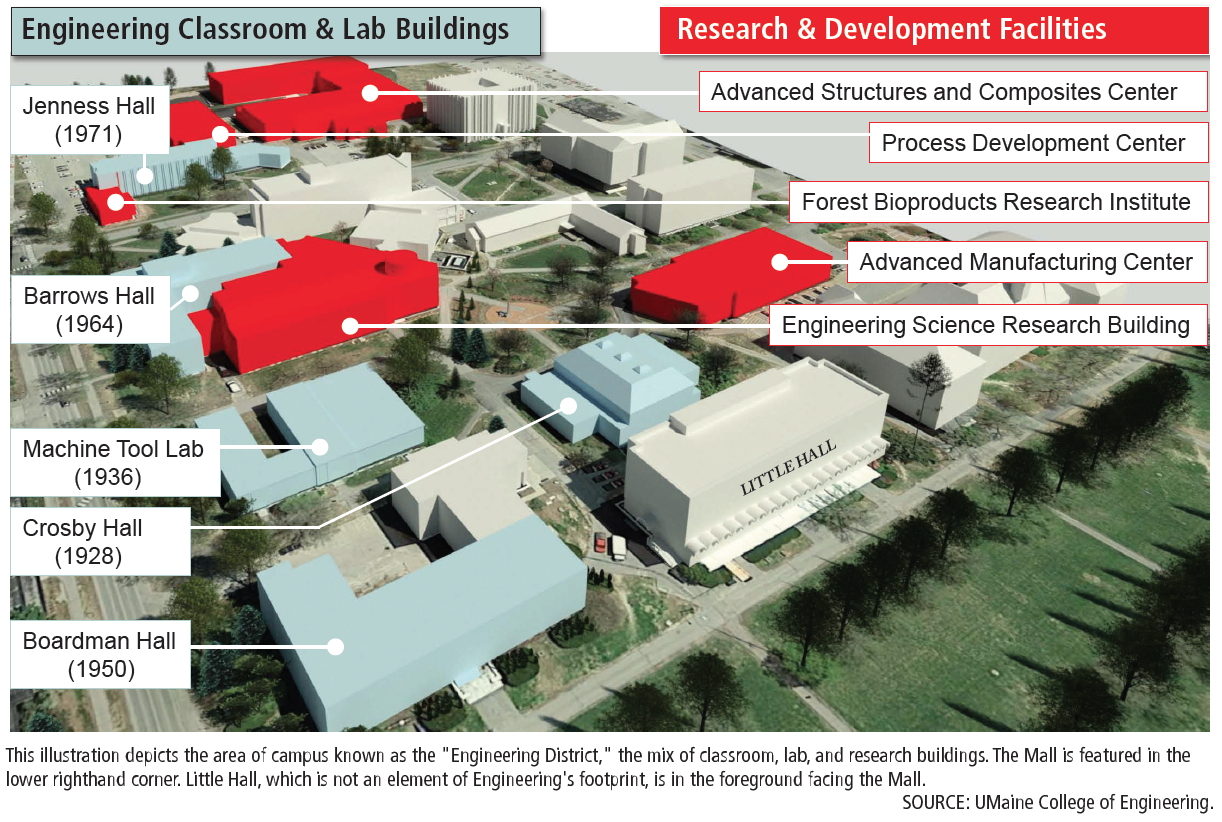

Engineering schools at other universities tout their “integrative” and “experiential” learning environments on their websites. Students gather in spaces that look more like engineering workshops than bland study halls. They certainly look different from UMaine’s Crosby Lab (circa 1928) and the Machine Tool Lab (circa 1936), and even the “modern” Jenness Hall (circa 1971).

The proposed Engineering Education and Design Center will meet the demands of modern learning, Humphrey says, with cutting-edge teaching labs, collaborative classrooms, and inviting spaces where student teams can brainstorm the next great idea. Electrical engineering students will be able to work hand-in-hand with chemical, mechanical, and construction engineers, “like they do in the real world,” Humphrey says. “Right now, students do this in cubby holes squirreled away in various buildings,” like students have been doing for generations.

Humphrey, who expertly balances the practicality of an engineer and the vision of a dean, remembers his first office as a new faculty member at UMaine in 1986. It was in Boardman Hall (circa 1955). His office, along with another faculty office and a classroom for 48 students, ran on one 20-amp circuit. “We were able to squeeze in two more circuits to serve the third floor,” he says, but construction experts have told him that they could do no more; rewiring the 62-year-old structure—running electrical conduit through its walls and floors, like inserting a new nervous system in a Baby Boomer—would not be practical or cost effective.

Today, “plug-in” is part of the American, if not global, lexicon, and devices that need to be electrically charged by plugging in are ubiquitous.

The Engineering Education and Design Center, Humphrey says, will be a place the students want to go, where they can plug in, get a snack, and work together. “This is going to be their space. When we give tours to prospective students, this will be our centerpiece.”

Maeve Carlson, a sophomore civil engineering major from Wiscasset, is one of the students who has to find a place in the library or in a dorm’s common area for her and her friends to study. Having a facility like the Engineering Education and Design Center would be “an amazing environment.” It would also be a point of pride.

“If UMaine adds this investment it will only strengthen the strong reputation of UMaine’s dedication to its students,” she says. “This makes us graduates look good, too, because we [attended] a school known for investing in their strong engineering program!”

After the Engineering Education and Design Center is complete, the university will undertake the third step in Humphrey’s three-step plan: the five existing buildings will be rehabilitated, making them more energy efficient, replacing mechanical systems, and modernizing classrooms and labs. The design center will be used as flex space while the other buildings are renovated.

Humphrey’s vision for the new building is a versatile facility, one with open spaces that let students work together on capstone projects and laboratories that can accommodate different disciplines depending on demand, from mechanical to biomedical to electrical. And, the building will be “durable.” “If you come back to UMaine in 100 years, the Engineering Education and Design Center will still be a critical facility,” Humphrey says.

Economic impact

More importantly, the new facility will pay for itself through the taxes paid by engineers attracted to UMaine and who stay and help Maine companies grow, Humphrey says.

The long-term payoff of a new engineering facility “is that we create more high-paying jobs in Maine,” Humphrey says. “If we count additional jobs that will be created by the work of engineers, the payback on the new facility will be even greater.”

His last point underlines the return on a statewide investment: It’s not just for engineers, but also for people whose jobs rely on the skills engineers bring to the table. Engineering has a direct economic impact on Maine’s GDP of $2.2 billion, a number that grows to $3.7 billion when indirect impact is factored in.

His last point underlines the return on a statewide investment: It’s not just for engineers, but also for people whose jobs rely on the skills engineers bring to the table. Engineering has a direct economic impact on Maine’s GDP of $2.2 billion, a number that grows to $3.7 billion when indirect impact is factored in.

From Pratt and Whitney in North Berwick to Proctor and Gamble in Auburn to Old Town Canoe in Old Town, companies that produce products need engineers. “If we’re going to have companies like that in Maine, we have to have engineers,” Humphrey says.

Despite a 74% growth in undergraduate engineering students from 2001 to 2014, the demand for engineers in the workforce far exceeds the number of engineers graduating in a given year.

Finding young engineers to fill open positions is “pretty challenging,” says Jim Wilson ’92, a senior principal and senior project manager for Woodard and Curran, a company founded in Maine by UMaine alumni that is growing nationally.

The State of Maine’s sluggish investment in infrastructure has limited the need for engineers to work on the types of projects in Maine that Wilson works on, but, he says, there’s still a great need for engineers to work in Maine. Eighty percent of his workload is outside the state, “But the revenue is generated in Maine, and the tax base it supports is here.” Other Maine-based engineering firms have also expanded geographically.

Woodard and Curran relies on UMaine for engineering recruits, so it is critical the university maintains its competitive edge with top-notch, modern facilities.

“While on one hand we’ve focused on more opportunities for STEM education and intriguing kids to wanting to have STEM professions, right now the UMaine facilities haven’t delivered on that goal,” Wilson says.

“While on one hand we’ve focused on more opportunities for STEM education and intriguing kids to wanting to have STEM professions, right now the UMaine facilities haven’t delivered on that goal,” Wilson says.

Meanwhile, other New England states have invested nearly a half-billion dollars in new engineering space at their public universities, Humphrey says.

Falling behind educationally leads to falling behind economically. “To not allow (UMaine) to be competitive with other schools in our region affects the ability of the university to deliver on what the local economy needs to be successful,” Wilson says.

On the flip side, investing in a competitive engineering program “is one way to attract and keep young people who will make good wages and care about the environment,” Wilson says. And it will attract “the kinds of businesses we want to support for the demographic we want to keep.”

The Engineering Education and Design Center is the cornerstone of a new economy for the state, but unlike in Hollywood, making this dream come true requires more than movie magic. It will be the largest construction project ever undertaken at UMaine, but the cost, Humphrey says, is in the range of a new high school. The difference is impact: this UMaine building will serve the entire state, and, most importantly the companies and communities that rely on engineers.

The Engineering Education and Design Center is the cornerstone of a new economy for the state, but unlike in Hollywood, making this dream come true requires more than movie magic. It will be the largest construction project ever undertaken at UMaine, but the cost, Humphrey says, is in the range of a new high school. The difference is impact: this UMaine building will serve the entire state, and, most importantly the companies and communities that rely on engineers.

A combination of state bonds and private funding give the State of Maine the opportunity to have a hand in creating their future.

“For a project of this magnitude, funding needs to be a partnership between the State of Maine, the people of Maine, the businesses that employ our engineering graduates, and the graduates themselves,” Humphrey says. “We need to work together and provide the funding for this building.”

“We have to have the collective will to make this investment,” Humphrey says. “We have to make

this happen.”