Mother and child in front of their house in Varanasi, India. Photo by Yavuz Sariyildiz / Shutterstock.com

SHORTLY BEFORE SHE came to the University of Maine, Rachel “Rae” Binder-Hathaway ’12 read a book that would change the course of her life. It also ignited a passion to change the lives of countless women and families worldwide — first through her scholarship at UMaine and Harvard University, and today through her research and policy work with the United Nations and the World Bank.

That book was Banker to the Poor: Micro-Lending and the Battle Against World Poverty, written by Nobel laureate Muhammad Yunus. Yunus, the founder of Grameen Bank, is considered a pioneer of microfinance. The practice is designed to help alleviate poverty by providing small loans at affordable interest rates to the rural poor — primarily women — in developing countries.

“When a destitute mother starts earning an income,” he wrote, “her dreams of success invariably center around her children. A woman’s second priority is the household. She wants to buy utensils, build a stronger roof, or find a bed for herself and her family.

“A man has an entirely different set of priorities,” Yunus continued. “When a destitute father earns extra income, he focuses more attention on himself. Thus money entering a household through a woman brings more benefits to the family as a whole.”

“Reading Dr. Yunus’ words opened my eyes in a different way of development practice,” recalls Hathaway, whose current work lies at the intersection of behavioral science, gender equity, international economic development, and program evaluation. “In many parts of the world, there aren’t government safety nets, women’s families aren’t adequately supporting them, and they’re experiencing constraints that even men in poverty aren’t subjected to. If you empower women, put the earning capability in their hands, if you give them training opportunities, through that, women can raise themselves out of poverty.”

Though Hathaway experienced her own challenges on her path to UMaine, these women’s experiences stood in stark contrast.

GROWING UP IN Millinocket, Hathaway was surrounded by strong female role models. In her 20s, she lived in New York City and worked as a jazz musician and a real estate agent. She gave birth to a son, Jacob, and raised him as a single mother. And when she returned to her home state to pursue an education at the University of Maine, her family was there for her — pitching in to watch Jacob during intense study periods, and cheering her on along the way.

“I’m cognizant of the fact that not everyone has that level of support,” Hathaway says. “I’ve always been a planner, I’ve always had opportunities. I had a strong family base to lean on when things felt overwhelming. But I saw a lot of moms — particularly single moms — who didn’t have that safety net in place.”

When she read about the women in Yunus’ book, she wanted to learn more about their on-the-ground realities, struggles, and successes “up close and personal.”

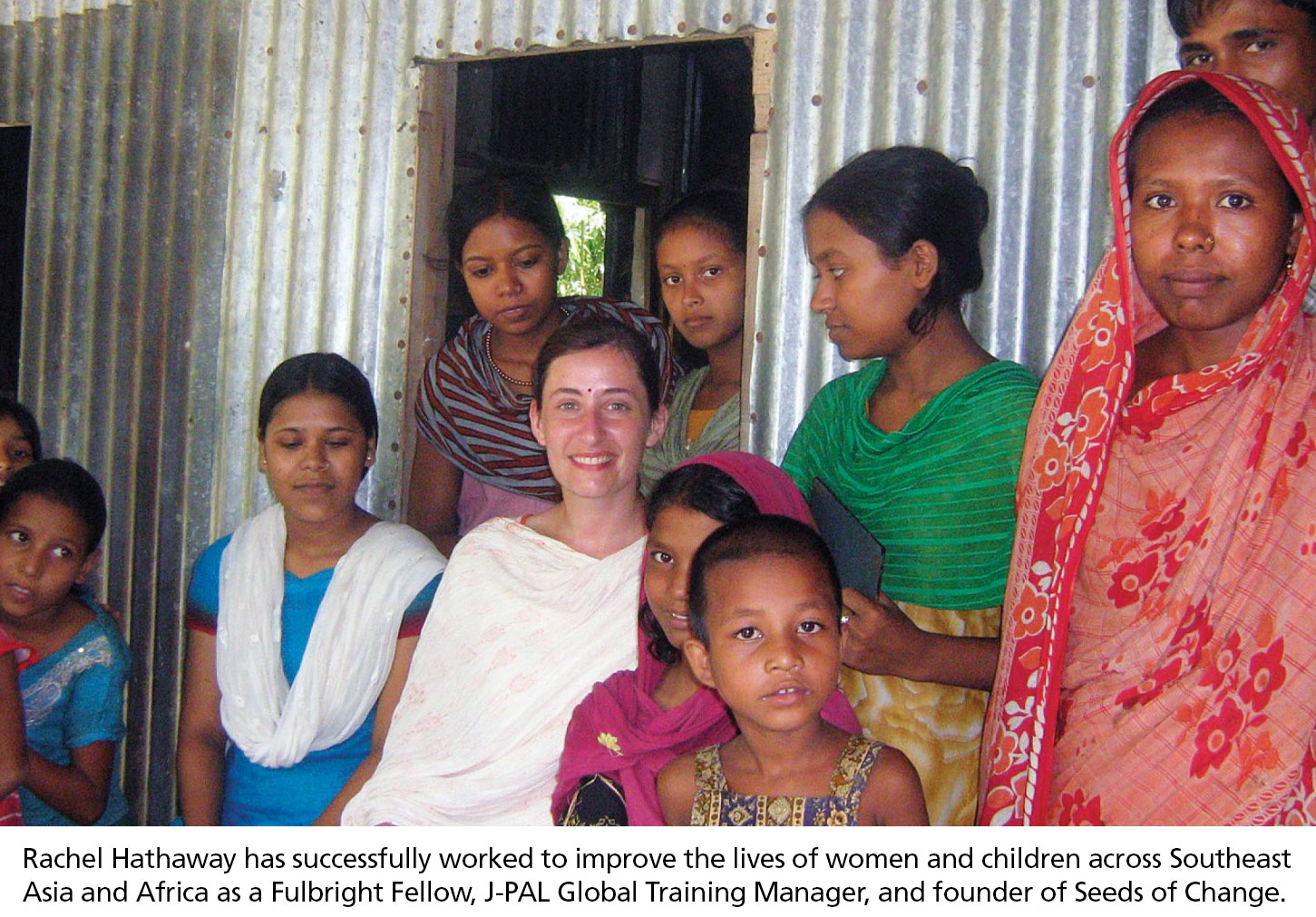

As part of a multi-year project that culminated in her Honors thesis at UMaine, Hathaway did just that. She wanted to learn as much as she could about microfinance, so she sought out a United Nations course on the topic and traveled to Bangladesh multiple times — first through a research project to work with Yunus at Grameen Bank, and later as a Fulbright Fellow to continue her comparative analysis of Grameen and BRAC, another microfinance enterprise.

“I had never been on the ground in a developing country,” Hathaway says. “I knew about the challenges that existed theoretically, but not personally. There was a lot of heartache but a ton of inspiration as well. You see these incredibly bright women who simply don’t have the same opportunities you and I have and you ask, ‘What can we do to help spark that opportunity?’ Advocacy and development work is not about going in and telling beneficiaries, ‘This is what you need.’ It’s about talking and listening, and then working together to figure out solutions.”

She was so moved by the street children of Dhaka living with one or no surviving parents, that she founded her own nonprofit, Seeds of Change, which provides educational and training opportunities to at-risk children and women in the developing world.

“I think this defines Rae,” says Dr. Richard Borgman, a professor of finance who served on Hathaway’s thesis committee and remains one of Hathaway’s closest friends and mentors.

“Seeing a problem with horrific human consequences … she does not sit idly but instinctively thought of a way to make a difference and, in this case, ultimately created her own organization to effect change.”

BY ALL ACCOUNTS, that drive to take action was typical of Hathaway’s life at UMaine and beyond. She arrived on campus as a nontraditional student and a single mom. She was focused. Inquisitive. Ambitious. She graduated with three degrees — in financial economics, finance, and accounting. She asked to join the Honors College because she felt it was important to her academic trajectory. She earned a Fulbright Fellowship. She was the top student in finance and business. Oh, and she graduated as class valedictorian and delivered her commencement address via Skype from Bangladesh.

“She was not here to waste time, but rather to get everything she could out of her experience,” recalls Borgman. “I said at the time, she was the best we have, and would be the best in most other places as well.”

Hathaway went on to earn a master’s in public administration, with a dual concentration in behavioral economics and international development from Harvard University’s Kennedy School, where she won the Dean’s Award for Excellence in Student Teaching. As a research and teaching fellow at Harvard, she honed her quantitative analysis skills alongside highly regarded academics including behavioral economist Iris Bohnet, author of What Works: Gender Equality by Design.

“Rachel had always been interested in inequality and gender issues,” Borgman says. “Now she was working on important projects with real impact: for example, behavioral economics programs for the Australian and Nigerian governments.”

That experience opened the door to opportunities with a global scope. In 2018, she became global training manager for the Jameel Poverty Action Lab at Massachusetts Institute of Technology, whose founders recently received the Nobel Prize for Economics.

In 2019 she joined the World Bank as a consulting economist on the Nigerian National Social Safety Nets project. The program will provide $1.8 billion in funding for targeted cash transfers, behavior-changing training, and incentives to five million of Nigeria’s most vulnerable families by 2021. Hathaway oversees 300 staffers who are focused on assessing the outcomes of development interventions, including youth employment, workforce inclusion, and gender equity.

“In a society that tends to undervalue economic inclusion for women, where women are typically working as unpaid caregivers, we’re seeking ways to promote women’s inclusion, through the provision of training development and updated social norms at the household level, that allow them to better integrate into the workforce,” Hathaway explains. “When half of the society is not economically integrated, they are excluded from contributing meaningfully to economic growth. We’re encouraging families to consider the caregiver, who is often a woman, apply for the grant to add to the family workplace dynamic.”

Hathaway spent six months in Nigeria, where she and her team conducted surveys in six of that nation’s states. She has since returned to New York, where she works as a consultant for the United Nations — both with UN Women and the UN Development Program. Through UNDP, she’s part of a small global gender team. She is charged with a giant task: building a global strategy that will inform policies for inclusive economic growth in more than 170 countries worldwide.

“I’m fortunate to be working on several different sizable projects,” Hathaway says, and she’s considering other consulting opportunities as well.

“All of Africa is looking to our World Bank team to see if this project succeeds. There’s a great deal of pressure to get these things right.”

Hathaway’s level of influence and commitment is no surprise to her professors and friends at UMaine.

“Her worldview, combined with her experience, skills, and knowledge, have enabled her to take fuller advantage of all these things to really become an agent of positive social change,” says Dr. Melissa Ladenheim, associate dean of the Honors College. “So much of this work is relational. Being skilled at developing and stewarding relationships is key and Rachel is good at that. She sees the bigger picture. It’s not about her career, it’s about being a change agent.”

HATHAWAY’S commitment to positive change is matched only by her commitment to her son. Each step in her career path — from jazz musician to real estate agent to Honors scholar to global consultant — was taken with Jacob in mind. She described her focus as a parent in “Mothers in Honors,” a 2013 paper she co-authored that was published in the Journal of the National Collegiate Honors Council.

“I have always been a motivated individual, but motherhood shifted my focus away from personal wants and needs,” she wrote. “My priorities now revolved around the needs of my son, and, because I was a single parent, this need to provide was heightened dramatically. My path has not always been easy, yet I am glad to have walked a few miles in these shoes, thus opening my eyes to the plight of mothers everywhere, especially those who struggle to provide for their families with little hope of realizing their aspirations for a better life. I carry them with me.”

“I knew her as a student and a mother and found her to be remarkably focused, passionate, and empathetic,” says UMaine Professor Margaret “Mimi” Killinger ’04 Ph.D. “Rae is special in my mind in that she took that sense of purpose and intellectual commitment and expressed it on a global scale, and she brought Jacob along with her and enriched his life.”

Jacob drew on his experiences in Bangladesh with Seeds of Change for his college essays, and he plans to study finance at the University of Massachusetts.

“Spending time in a third-world country opens your eyes to the struggles people all over the world are going through every day,” he says. “It’s made me a lot more understanding.”

When asked to describe his mother in one word, Jacob is quick to answer: determined.

“She’s strong-willed, to say the least,” he says with a laugh. “She’s really thoughtful and she always wants the best for other people. … The fact that she graduated as valedictorian, earned a Fulbright Scholarship working with Grameen and went to Harvard after all that shows that it’s never too late to follow your dreams, as long as you have the determination and the skills to do so.”