DR. PAUL PLOURDE’S LIFE story is a powerful one: that of a small-town teen who left home to attend college and went on to use his talents and education to save thousands of lives and shift the therapeutic practices of medicine.

Plourde, the recipient of the Alumni Association’s 2021 Dr. Bernard Lown Humanitarian Award, is an internationally renowned specialist whose ability to straddle the worlds of patient care, scholarship, drug research and development, and regulatory hurdles led to revolutionary advances in cancer therapies.

Under his leadership, the pharmaceuticals tamoxifen, anastrozole and fulvestrant have become ubiquitous anti-cancer hormone therapies for individuals with breast cancer. Similarly, he led efforts to gain approval of the drug Erwinaze as part of the treatment regimen for children with acute lymphoblastic leukemia (ALL) that dramat-ically increases the survival rate of individuals with the disease.

Like Dr. Lown, the 1942 UMaine graduate whose many accomplishments include the development of the life-saving direct-current heart defibrillator, Dr. Plourde has changed the world. Without exaggeration, the two of them are among a relatively small number of people, past and present, whose contributions to medicine impacted literally hundreds of thousands of lives.

Humble Beginnings

Plourde grew up in Van Buren and Madawaska, small towns in the St. John Valley on Maine’s northernmost border with Canada.& Following his high school graduation, he enrolled at the University of Maine.& He majored in chemical engineering, thriving on the intellectual challenges of his education and experience. He completed his undergraduate program in 1973 and his graduate degree one year later.

“[UMaine] was a perfect blend, where all of a sudden a new world opened up to me,” he said, reflecting on his days in Orono.

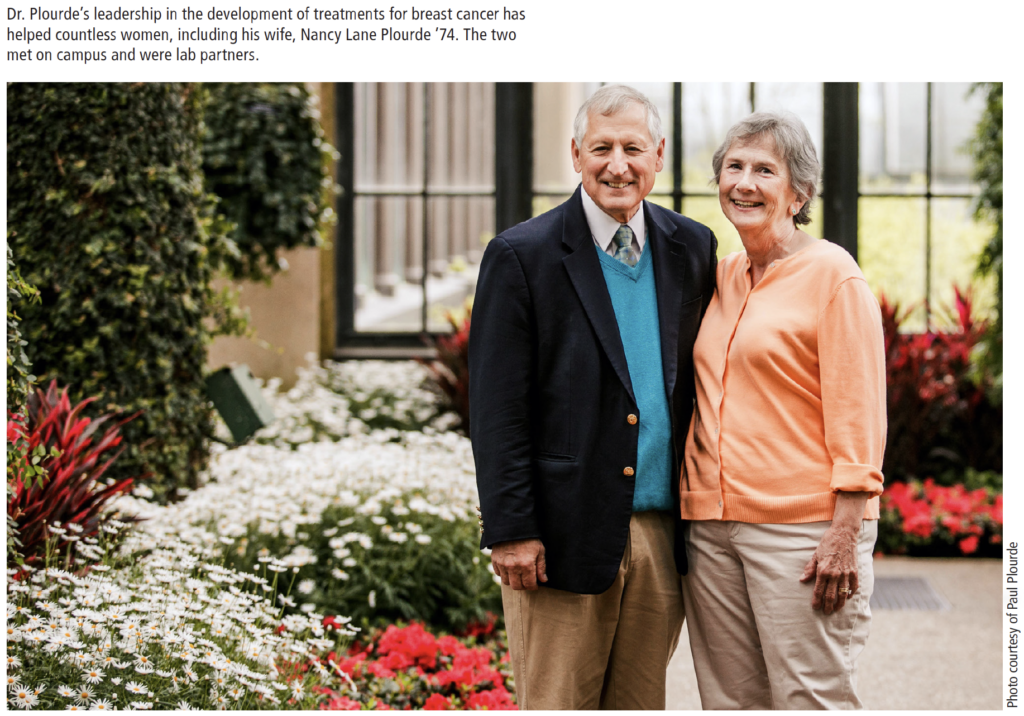

Among his greatest discoveries in that “new world” was a fellow student, Nancy Lane `74, whom he met through one of his Sigma Phi Epsilon fraternity brothers, James Tammaro. Plourde and Lane became lab partners in an endocrinology course and married the following year.

The two attended the University of Vermont School of Medicine, from which they both earned medical degrees. Paul Plourde conducted his internal medicine residency at Penn State University Medical Center in Hershey, followed by another two years of specialized training there in endocrinology. He started a private full-time endocrinology practice in Lancaster, Pennsylvania, before embarking on a 23-year career with what ultimately became AstraZeneca, a global pharmaceutical giant. For a number of years while in the pharmaceutical industry, he continued seeing and caring for patients.

At the time it was uncommon for a medical doctor to venture into the field of pharmaceutical research, Plourde explained. But it allowed him to maximize the complementary attributes of his training in chemical engineering and medicine. And though he didn’t anticipate that working in the pharmaceutical industry would become his life’s work, it did — and with dramatic results.

As is frequently the case in medical research, the therapies Plourde helped develop arose out of failures and disappointments he experienced earlier in his career. For example, he spent three years working to develop a drug to treat neuropathy in those with diabetes.

“I had to tell people I was so good at my job that I proved the drug did not work. But proving a drug is not effective saves many patients from taking a medicine that will only give them side effects without any benefits,” Plourde noted in reference to those efforts.

But he had more success with tamoxifen, a pharmaceu-tical originally developed in the U.K. in the late 1950s as a hormone-based contraceptive. A series of studies determined it was suboptimal for those purposes. However, those results led to further research that found the drug could work to treat breast cancer.

In the 1970s and early 1980s, the first trials with tamoxifen showed it could be effective as a treatment for metastatic breast cancer.& Building on the earlier work of others, Plourde and his research team pursued further development of the drug for the treatment of breast cancer that had not yet spread to other organs of the body.& $e results of these trials were submitted and approved by the FDA. Consequently, tamoxifen became one of the world’s most prescribed pharmaceuticals and improved countless lives.

Plourde also pursued the development and global regulatory approval of another hormone-based cancer treatment: anastrozole, a revolutionary anti-cancer therapy that blocks the production of estrogen, which cancer cells depend on to grow. He coordinated the conduct of clinical studies, analyzed the data and prepared the study reports for submission to global regulatory authorities.& In the U.S., Plourde utilized a new program under then-President Bill Clinton to fast-track review of cancer treatment medicines by the Federal Drug Administration (FDA).

“And within 43 days, [anastrozole] was approved by the FDA,” explained Dr. Richard Santen, emeritus professor of medicine at the University of Virginia and a person Plourde cites as his mentor. “It’s a record that hasn’t been surpassed since then. He was in the right place, at the right time, with the right idea, and the right regulatory documents. $at’s quite unusual and it took substantial talent and training to do that.”

Anastrozole’s Impact

Dr. Gershon Locker, a colleague of Plourde’s for more than 20 years and his manager at AstraZeneca, described Plourde’s groundbreaking work on anastrozole.

“Paul’s contribution to the rapid development of anastrozole gave women new alternatives to allow them to avoid or delay chemotherapy,” he wrote in his letter nominating Plourde for the Lown Humanitarian Award. “The rapid development of the drugs remains unparalleled in novel drug development.

“For those who have advanced breast cancer — incurable — you’d like to develop therapies to make their lives longer and better,” Locker added in an interview. “For those patients with curative cancer, you’d like to decrease the likelihood of it ever coming back. Ultimately, you’d like therapies for preventing cancer from occurring in the first place.

“Paul’s triumphs were in all three potential goals,” Locker declared.

The treatment protocol later served the healthcare needs of Plourde’s own family. Both his mother, wife, and aunt used either tamoxifen and/or anastrozole, he said.

His mother took tamoxifen, his first drug, and “did well for about three or four years. But I remember attending a meeting when I was called out because my mother was calling. The first thing she said was, ‘It came back.’”

Plourde said his mother’s doctor recommended chemo-therapy. He immediately flew down to Florida to speak with her oncologist, bringing along an article he had written about the results of the aromatase inhibitor, anastrozole. Until that moment, the oncologist had not been familiar with its regulatory approval.

His mother was treated with the drug and gained another two quality years of life before succumbing to breast cancer, Plourde said.

Over a decade ago, Dr. Nancy Plourde, Plourde’s wife, was diagnosed with breast cancer. She took anastrozole and subsequently tamoxifen and has now been cancer-free for 12 years.

“There are very few families that aren’t touched by breast cancer,” Plourde said. “It has been personally rewarding to have made an impact on the people I love.”

“Even to this day, people on the teams I led will sometimes call and say, ‘My aunt has breast cancer, or a friend’s child has leukemia and guess what drug they’re on? A drug we developed’. It leaves you with a very warm and content feeling that drugs we labored to develop are benefitting so many people. “

A Leukemia Breakthrough

Plourde, who rose to become the vice president of oncology at AstraZeneca, decided to leave the company in late 2007. He was recruited by Dr. Timothy Corn to join a United Kingdom-based startup called EUSA Pharma. Corn flew to New York to interview candidates to lead U.S. medical operations.

“Paul stood out at the interview for his enthusiasm, commitment to patients, and his experience in developing drugs in oncology,” Corn said. “We established a great relationship immediately, and it was clear that he would be able to work independently to build our medical function in the U.S.”

Corn said Plourde was “respected enormously as a leader” and “became a key figure in the company.

“The plight of children with leukemia, especially those who would be candidates for treatment with our drug, was the basis for his mission,” he explained.

EUSA developed a treatment to help individuals with acute lymphoblastic leukemia (ALL), the most common cancer in children. $rough Plourde’s leadership and expertise, EUSA gained FDA approval of the drug Erwinaze. Children with ALL are treated with chemotherapy and an enzyme called asparaginase made by a bacteria. Asparaginase lowers the level of asparagine, an amino acid that leukemic cells need to survive.& By lowering asparagine with the enzyme, leukemic cells die.& But many of those children develop an allergy to this asparaginase and the treatment has to be discontinued.& Erwinase is also an asparaginase enzyme but is made by a different bacteria and can be used in children who developed an allergy to the previously administered asparaginase.

Erwinaze is highly effective in reducing the level of asparagine in the blood and thereby promotes the destruction of leukemia cells. Being able to continue asparaginase treatment with Erwinaze in children with leukemia as part of the prescribed therapy, doctors can significantly increase the number of patients who are cured.

The introduction of Erwinaze as part of the standard protocol for treating childhood leukemia dramatically increases the survival rate of patients. According to EUSA’s Corn, nearly 1,400 patients were treated with Erwinaze in its first four years of use.

“That’s like one [patient] a day,” he said. “There aren’t many doctors who can say they’ve given a potentially life-saving cure to one patient a day,” referring to Plourde’s role in developing the new therapy.

According to Plourde, the survival rate for childhood leukemia when he first started medical school in the mid-1970s was 10-15 percent. $e use of chemotherapy as a treatment increased the percentage, but the FDA’s approval of Erwinaze in 2011, along with other compounds, has increased the survival rate to more than 90 percent, he said.

While many laud Plourde for his advancement of successful cancer therapies, he characteristically redirects the praise to the brave patients who have participated in countless clinical trials for experimental drugs over the years.

“None of this would’ve been possible with the dedication and help of courageous patients,” Plourde said. “It’s those people who have volunteered to be in clinical trials that have made the greatest impact.

“Any person volunteering for a clinical trial [is] taking that unknown risk for a potential benefit, not only for themselves but for others in the future,” he continued. “I really respect what they have done.”

Plourde also emphasized the collaborative nature of research and the role colleagues have played in his successes.

“Most of my accomplishments have been as part of a team,” he explained. “I could never do anything in breast cancer or leukemia [research] without the support of my bosses, my team members, the investigators, and most importantly the patients that participated.”

While those factors are valid, EUSA Pharma’s Corn, its former chief medical officer, stated his sense of Plourde’s role more emphatically.

“It is fair to say that there are a significant number of Americans who are alive today as a direct result of Paul’s academic rigor, his compassion for patients, and his outstanding ability to bring people together,” he said.

Still, exhibiting the modesty often associated with natives of Maine’s St. John Valley, Plourde continued to downplay his own role in achieving medical breakthroughs.

These life-saving achievements, he emphasized, should be recognized as “a true team effort that I just happened to lead.” M