Cardiothoracic surgeon Bruce Leavitt ’77 donates his time and talent to saving lives

By Will Cleveland ’07G

WHEN BRUCE LEAVITT arrived at UMaine in 1973, his intent was to prepare himself for a career as a dentist. But that soon changed.

“I went to a dental clinic and thought, ‘This isn’t for me.’ And then my adviser said, ‘Your grades are good enough to probably get into medical school.’

“I liked the idea of being a doctor,” he said. “I liked this idea of helping people, so I applied and got into the University of Vermont Medical School” following his graduation from UMaine in 1977.

Today Leavitt is an internationally renowned surgeon specializing in heart surgery. His decision to pursue medicine, not dentistry, has made a world of difference. It has enabled and inspired him to travel the globe as part of humanitarian organizations that provide life-saving health care to people in economically underdeveloped regions of the world — notably Rwanda, Sri Lanka, and Nigeria.

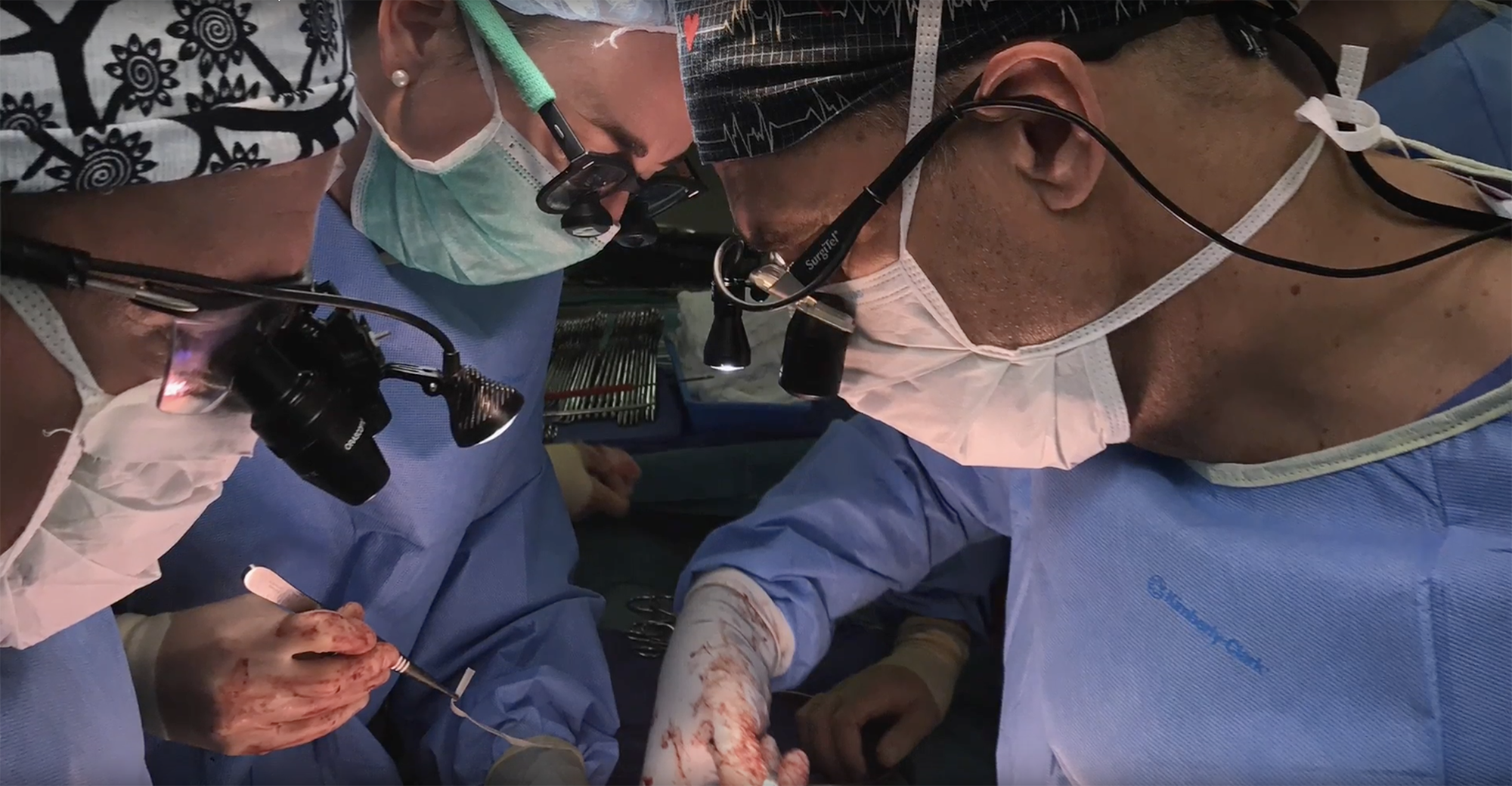

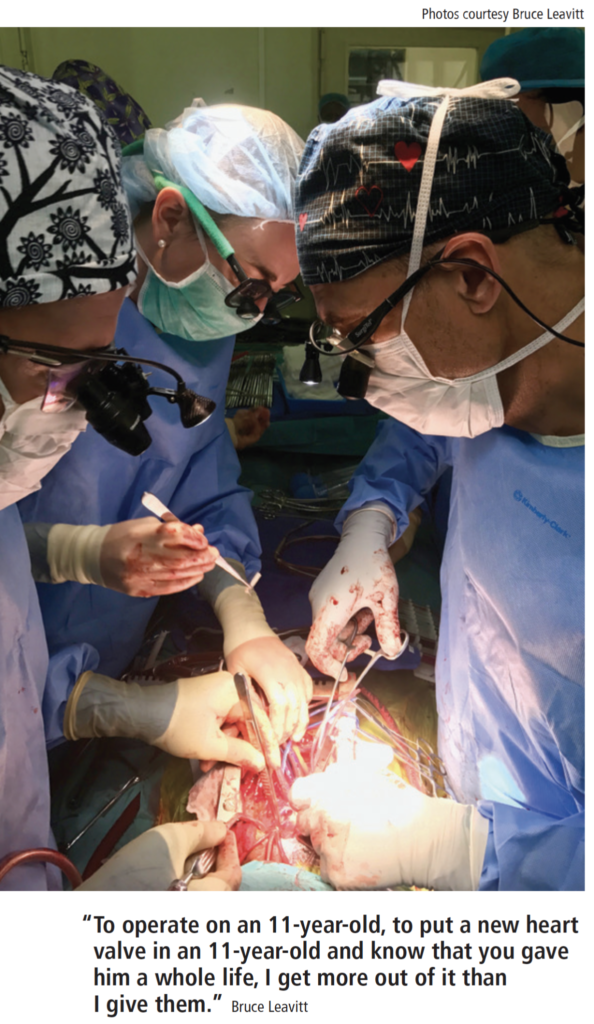

“Over there, if we don’t go, those people don’t get surgery and they’ll probably die from their disease,” he said. “We’re going over there and serving an unmet need. To operate on an 11-year-old, to put a new heart valve in an 11-year-old and know that you gave him a whole life, I get more out of it than I give them.”

LEAVITT ENROLLED AT UMaine following his graduation from Waterville High School in 1973. He quickly became active on campus, joining Phi Eta Kappa fraternity and volunteering as a deejay at WMEB-FM, the student-run radio station. Prior to his senior year he was selected for membership in Senior Skulls, the prestigious campus honor society.

Though he considers himself a member of the Class of 1977, Leavitt actually completed his UMaine degree a semester early, in December of 1976. When he started medical school in Vermont, Leavitt originally envisioned becoming a general practitioner. His direction changed when, in one of his first classes, he watched a video of heart surgery. He was transfixed.

“I said, ‘That was the coolest thing I’ve ever seen,’” Leavitt said. And as a result, his career path took a different direction.

He finished medical school in 1981, followed by a residency at Portland’s Maine Medical Center and one at SUNY Health Sciences in Syracuse, NY.

Since 1988 Leavitt has been a faculty member and surgeon at the University of Vermont’s Larner College of Medicine. Currently he serves as the chief of cardiac and thoracic surgery as well as professor of surgery. He has received many awards and recognitions, including his service in 2017 as president of the prestigious New England Surgical Society. (He titled an address he gave at the organization’s annual meeting as “Zen and the Art of the New England Surgeon,’ paraphrasing the title of one of his favorite books and a reference to his passion for motorcycles.)

LEAVITT’S INTEREST IN offering medical care in under- developed regions of the world was sparked more than two decades ago when he joined colleagues from around the U.S. on a trip to China, where they taught doctors at a rural hospital how to perform heart surgery. The experience had a great effect on him, igniting a desire to continue those efforts. Following similar international trips of that nature, he took an interest in becoming part of Doctors Without Borders, the international organization which received the Nobel Peace Prize in 1999. He also became involved with Team Heart, another organization that provides humanitarian healthcare services in developing countries.

Through Team Heart, Leavitt has traveled to the east African nation of Rwanda, where for the past six years he and his col- leagues have performed nearly 100 heart surgeries.

Their work is truly life-saving: Rwanda is a nation of nearly 12 million people, but, as Leavitt explained, it has just five cardiologists and no cardiac surgery facilities. Team Heart performs screenings, heart operations, and conducts workshops with local medical staff. Leavitt leads a team that treats adolescent patients. His wife, Anne, joins him on these yearly trips.

“He’s compassionate and he cares,” shared R. Morton Bolman, Leavitt’s cardiothoracic colleague at Vermont. Bolman founded Team Heart with his wife, nurse Ceeya Patton-Bolman, in 2006. “He has become a big part of our team. He’s dedicated. He’s well-trained. He’s hard-working and he cares about his patients. He’s a great family person. He’s made a big personal commitment to this.”

“He’s a real renaissance man,” observed Dr. Mitch Norotsky, the medical college’s chair of surgery. “He’s got a passion for life…He’s got boundless energy for everything he undertakes.”

In 2009 Leavitt traveled to Sri Lanka, which was at the tail end of a 26-year civil war. Leavitt arrived in the South Asia island nation and got to work.

“There I was, operating in a tent in the tip of Sri Lanka on Tamils, mostly women and children who were injured in the civil war between the Sinhalese and the Tamils,” Leavitt related. “I would look and think, ‘Here’s this boy from Maine and I’m in a tent in a jungle on the other side of Earth, taking care of people who might die or be injured for life.’ It was just such an experience that it’s hard to explain how great and moving it was.

“We managed to help a lot of people,” he reflected.

The Sri Lanka trip was followed by a mission to Nigeria, where for a month he was the only trauma surgeon in a hospital. “Patching people up from gunshots, stab wounds, I just saw some unbelievable stuff,” he said.

UNDERSTANDABLY, LEAVITT HAS many admirers, including patients, students, colleagues, and other beneficiaries of his talents. But no one is more supportive and proud than his children: John, Allison, and Haley. Just before Leavitt departed for Sri Lanka, John, now 32, gave him a sealed letter and told him not to open it until he arrived. In the envelope was an aspen leaf John took from a tree next to his tent while he was camping in Colorado. The leaf was accompanied by a letter that said, “Dad, you always taught me to do the right thing. Going to Sri Lanka and helping those people is the right thing.”

Haley, 26, said that doing the right thing remains the most important lesson her father taught them.

“He instilled in us, even if it’s the harder decision, that you always need to do the right thing,” she said. “He instilled the importance of a hard work ethic, because hard work does pay off. And being kind to others and treating people with respect. You can really see that through his career choice.”