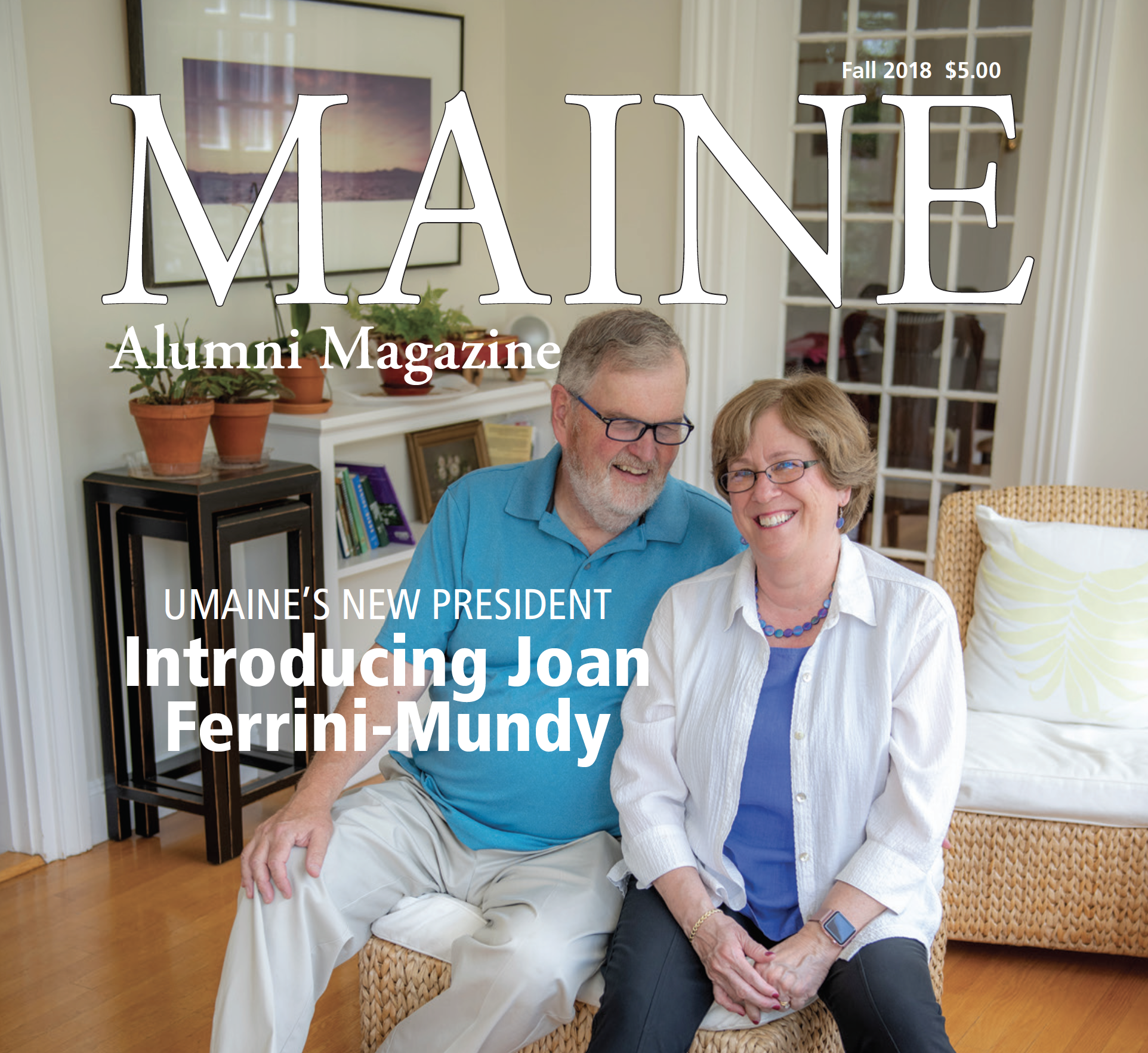

Multi-talented and multi-titled, UMaine’s new President has hit the ground running

JOAN FERRINI-MUNDY grew up learn- ing the importance of family, a work ethic, and education.

The Portsmouth, New Hampshire native also learned about Maine, because her father was in the second graduating class at Maine Maritime Academy.

“He had fond feelings for Maine because of his time there,” says Ferrini-Mundy, who has her father’s certificate of graduation framed and hanging in her UMaine office. “Dad going to Maine Maritime was a big step for the family. The wonderful experiences he had in this state were always part of the family lore.”

Today, as UMaine’s 21st president, Ferrini- Mundy has a leadership role in the state she now calls home. And a national voice. As leader of Maine’s flagship university in Orono and its regional campus in Machias, she brings to bear her 40-year career that has included mathematics teaching, nationally recognized STEM education innovation and research, and program development and administration at the National Academy of Sciences and the National Science Foundation (NSF).

Ferrini-Mundy also brings her passion for land grant universities. UMaine is her third, following the University of New Hampshire and Michigan State University. She understands and appreciates their statewide missions and “strong, solid values,” and has seen firsthand the difference their teaching, research and economic development, and community outreach make in people’s lives, on and off campus.

She is a champion of engagement — from seeing the “aha!” moments of students and teachers in the mathematics classroom to testifying before a Congressional subcommittee on the need to increase educational spending.

“I care about learning and opportunity for people to improve their lives,” she says. “Education is about helping people achieve their goals and dreams. There are many pieces to it, but in the end, people experiencing fulfillment, opportunity and productivity is important.”

Fundamental to theland grant mission is the commitment to bring the university’s research capacity and resources to the state for the improvement of quality of life at every level, Ferrini-Mundy says. “What’s also become clear to me (in my career) is that it is a two-way relationship. The state nurtures the university and brings to it the questions, challenges and the directions it is taking. I’ve seen it in a small and big state, and now in Maine.

“What I always appreciated is the proximity and interconnections of where a state’s needs, opportunities, and directions are, and where a university can be of help,” she says. “What’s wonderful about this is it’s all happening with a strong community and economic development focus, in the context of a research institution that is building new knowledge that will help drive all that and other things nationally. It’s a cycle: the research knowledge that grows is informed by efforts to implement it and by its translation into the classroom, and questions of the public and users in the state cycles back and shapes the research going forward. I like the dynamic of that kind of setting.”

FERRINI-MUNDY HAD BEENin federal government for nearly a decade, most recently as NSF’s chief operating officer, when she was recruited to apply for the presidency of the University of Maine and University of Maine at Machias. (Beginning in July 2017, the Machias campus became an administrative unit of UMaine. Ferrini-Mundy holds the title of president for both institutions.) She had lectured at UMaine a couple times in recent years, but it was as a candidate in the UMaine/ UMM presidential search process that she learned more about the breadth and depth of Maine’s primary research university.

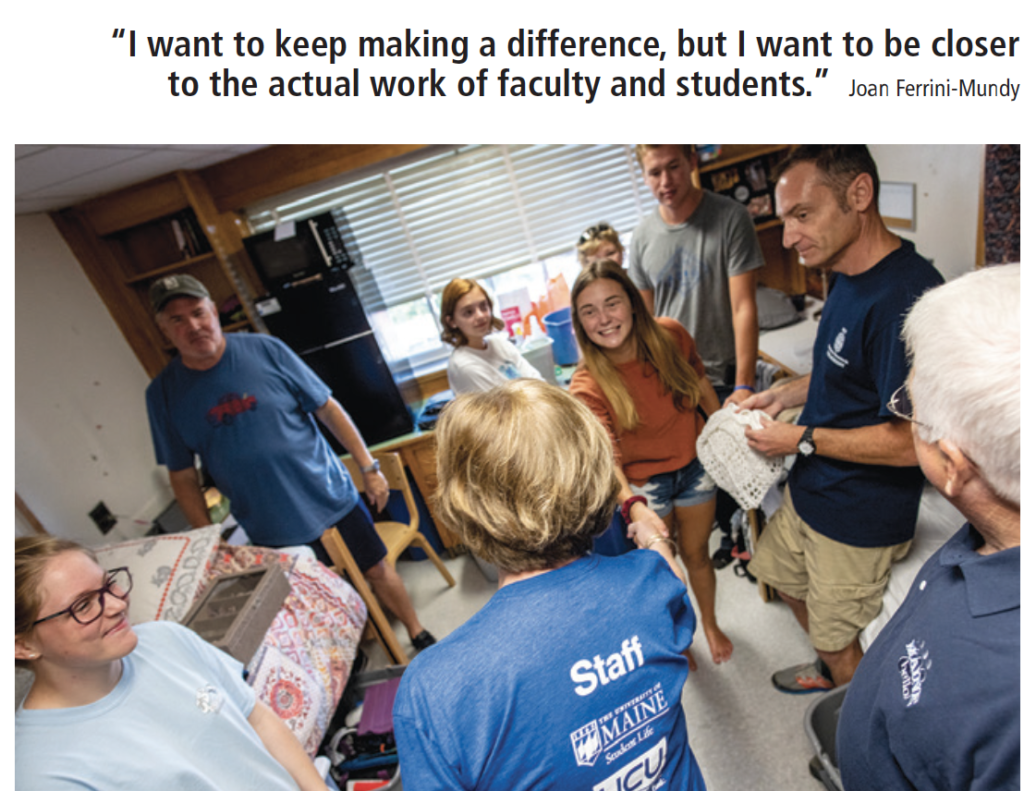

And she liked what she heard and saw. “I saw a level of belief in the university, that people are committed to UMaine and staying because it makes a difference,” Ferrini-Mundy says. “I learned that this is a positive, caring place, and I thought this would be a good transition for me from a very high level of government. I want to keep making a difference, but I want to be closer to the actual work of faculty and students.

“There’s also a familiarity with Maine because of my New Hampshire roots and the size of UMaine. I will have to learn more about this place and I like to learn.”

The challenges for higher education include the dramatic demographic shifts occurring nationally and in Maine, creating important opportunities, from exploring ways to

make a UMaine education more accessible more broadly in the state to building the diversity of the student body. Just as important, she says, is to remain ever-aware of how critical it is for the flagship university to be a strong, comprehensive research university.

“We have faculty ranging from earliest career faculty to some very senior people who are leading researchers and scholars in their field, and that’s essential to the vibrancy of a comprehensive university. Tied to that is commitment to excellent instruction, student success and learning. And we are strongly engaged in the state— from entrepreneurship to professional development of people in the workforce, supplying workforce in areas of great need in the state.”

In the first three weeks of this next chapter in her career that started July 1, Ferrini-Mundy couldn’t wait for the fall semester to begin.

“(I’ve already been) bowled over by the loyalty and generosity of alumni,” she says. “I also want to understand their stories — to know what it was about this university that meant so much to them. People have been influenced and shaped by this place. For the future, I have to understand the past and what made the difference for people. We need to pre- serve what has been so special and keep growing it.”

“(I’ve already been) bowled over by the loyalty and generosity of alumni,” she says. “I also want to understand their stories — to know what it was about this university that meant so much to them. People have been influenced and shaped by this place. For the future, I have to understand the past and what made the difference for people. We need to pre- serve what has been so special and keep growing it.”

FERRINI-MUNDY’S father, a steam engineer and Korean War veteran, was a lifelong employee of the Portsmouth Herald. In his youth, he was a Herald paper carrier. When he returned from the war, he was the mechanical superintendent in the newspaper plant, keeping the hot metal typesetting machines operating.

He could fix anything.

By the time the paper computerized and moved to digital printing, Azio Ferrini was the Portsmouth Herald’s general manager, functioning as publisher.

Ferrini-Mundy’s mother, Geraldine, worked briefly as a bank teller in Portsmouth and was the glue of the tight- knit family homefront.

“We had a warm, happy family with great Italian cooking,” Ferrini-Mundy says.

Ferrini-Mundy was the self-described “bookish older sister” of two “cool” younger brothers — Tom, who is now an attorney and former Portsmouth mayor, and Jim, a banker in Kennebunk.

“I was very competitive in a quiet way as a student,” she says. “My parents were the children of Irish and Italian immi- grants, and put great value in education and doing well in school. It was a high priority for them.”

In elementary school, when mathematics was obviously the strongest subject of the smartest student in her class, observing him, Ferrini-Mundy was determined she was going to “do math.” And she did — from choosing it for an honors class in the fourth grade to joining the high school math team.

“I always found math difficult, but my father was a puzzle and problem solver, and we connected a lot on math, as we did on so many things,” she says. “He helped me, and that was a closeness we had.”

But the smartest kid in the class wasn’t the only boy excelling in mathematics at school. There was also an “older” student (by three years) named Rick Mundy. On their first date — 48 years ago this past summer — Joan and Rick talked math.

“My goal was to be a math teacher in Portsmouth High School,” Ferrini- Mundy says. “I had had good teachers and I wanted to help kids. Then a professor at UNH, who was so confident in me, (helped me realize) that Portsmouth High School was not the only goal I could reach.”

That mentor was longtime UNH mathematics professor and department chair Richard Balomenos, who helped shape the course of mathematics education in that state. At the end of her undergraduate work (a bachelor’s in three years), he encouraged Ferrini-Mundy to pursue graduate school — an option that had never crossed her mind.

That was the start of her research on students’ learning of calculus and a new goal — teaching at UNH. It also was her first glimpse of the hallmark community engagement of land grant universities.

“In mathematics and math education, UNH had a strong public orientation,” Ferrini-Mundy says. “Professors were active in the state math teachers’ association. I saw the commitment of teachers to making a difference, and the difference I made in bringing professional development (in mathematics education) to them. It was clear that you can make a difference working with people who care about — and are good at — what they do.”

FERRINI-MUNDY received a Ph.D. in mathematics education in 1980, and spent the next two years at her alma mater doing postdoctoral research and implementation on gender equity in mathematics and science. She taught mathematics for a year at Mount Holyoke College, then returned to UNH to teach for 16 years.

“I learned it’s hard to be a really good teacher,” says Ferrini-Mundy, reflecting on the skills learned in her long teaching career that have informed her leadership at state and national levels. “It takes constant attention. It takes work and willingness to learn new things, and learning how to listen to students. One of my bosses once told me that everything is education — in any interaction you have, there’s learning going on.”

In 1989, while on the UNH faculty, Ferrini-Mundy had her first appointment at NSF as a visiting scientist, part of the foundation’s rotator program. From 1995–1999, she directed the Mathematical Sciences Education Board of the National Academy of Sciences, and also spent two years as associate executive director of the Center for Science, Mathematics, and Engineering.

She was recruited by Michigan State University in 1999 and stayed for 12 years to teach, conduct research and outreach in STEM education, and serve in administration. During that time, she also had two other NSF appointments, including one as inaugural director of the Division of Research on Learning in Formal and Informal Settings in the Directorate for Education and Human Resources.

In 2011, Ferrini-Mundy was named assistant director of the NSF education directorate and, by June 2017, COO.

At Michigan State, the National Academy of Sciences and NSF, Ferrini- Mundy was collaborating with national and international leaders in STEM education. And she shared her expertise and leadership. Among the important lessons from those years: how putting together groups of people with expertise and commitment can bring about serious change. She also learned how leaders make courageous decisions in the most challenging of situations. And the importance of constructive criticism and honesty.

“Leadership is about being clear about what you care about and what you’re working on is critical,” says Ferrini- Mundy. “You need to make sure you have the smartest, best thinkers and most committed people in the room who will offer alternatives and push back, who are not worried about who gets credit.

“I bring strong ideas of my own, but I’m a good listener, and I’m always asking how we can make it better and get to the next level,” she says. “That’s what’s engaging and exciting about work and life.”