PENOBSCOT AMBASSADOR Maulian Dana ’06 learned early on to speak her truth. Dana feels the voices of her ancestors running through her blood and bones. Appointed in 2017 as ambassador to the Penobscot Nation, she endeavors to honor the past and address present-day tribal issues — all while keeping her eyes focused on the future.

“I come from a long line of tribal leaders, and I was raised by strong women,” Dana says. “Both of my grandmothers had leadership positions in the tribe, and my father was Penobscot chief when I was a teenager. Seeing my dad’s experiences as chief—there were some dramatic and scary moments—helped shape who I am today.”

Soft-spoken and insightful, Dana, 35, took the reins of leadership at an early age. After serving a year on the Penobscot Tribal Council (the tribe’s decision-making board), the newly created ambassador position presented itself. “The work I’ve been doing for most of my life led up to this. [The job] feels like a perfect fit and I am grateful to be chosen,” she says.

As ambassador, Dana has embraced all aspects of the position. From talking with civic and school groups to meeting with politicians and government officials, she uses a multi-faceted approach to strengthen the political profile of the Penobscot Nation.

“Maulian is a tireless advocate for our people,” says Donna Loring ’86, who is Dana’s great-aunt, former tribal representative to the Legislature, and a 2017 recipient of an honorary doctorate from UMaine. “She has vision and imagination along with intelligence. I consider her the consummate diplomat.”

In the very public role as ambassador, Dana carries on work that began in her teens and now unfolds on a larger canvas. Dana, who earned a political science degree at UMaine, was instrumental in the successful effort to legislatively change Columbus Day to Indigenous People’s Day educating town councils and the public on the history of genocide and mistreatment of Maine’s native people and its roots in the subjugation of the continent’s indigious populations. Initially Maine cities such as Portland, Brunswick, and Orono adopted the change at the local level. But in 2019, Maine’s Legislature and Governor approved the change statewide.

“There is power in a name and in who we choose to honor,” explained Maine Gov. Janet Mills in April as she signed the change into law. “Today, we take another step in healing the divisions of the past, in fostering inclusiveness, in telling a fuller, deeper history, and in bringing the State and Maine’s tribal communities together to build a future shaped by mutual trust and respect.”

Standing behind Mills at the occasion, literally and figuratively, was Dana.

Early Motivation

Dana earned notoriety in Maine and beyond as the local founder of the “Not Your Mascot/Maine” movement in Skowhegan and other towns. She clearly remembers how it began one winter day in her early teens, watching the televised state basketball tournament with her father.

“It was the Warriors vs. the Indians. People were covered in fake war paint, whooping and dancing in a really offensive way,” she says. “I turned to my dad and said, ‘Is that how they think of us?’ That was my wake-up call.”

By the time she was 16 and a student at John Bapst High School in Bangor, Dana began visiting schools and partic- ipating in panel discussions, explaining that Indian mascots demean her heritage. She often faced boos, catcalls, and angry shouts, but the experiences strengthened her resolve. Few Indian mascots remain in the state today, and she intends to persist until they are all eradicated.

“I learned early on to speak my truth,” she says. “I know Indian mascots are harmful and disrespect our culture. When things get hard, I remember facing those angry crowds when I was a teenager, and I find my courage.”

Other pressing issues that came with the ambassador job include the tribe’s struggle over watershed rights to the Penobscot River, the opioid crisis, and a recent surge in overt racism. Driving all of her work is the enduring fight for recognition of the Penobscot Nation’s sovereignty.

“Maulian is persistent. Beneath that quiet exterior lies the spirit of a badger,” says Loring, whom Dana names as an influential mentor. “She comes from a long line of Wabanaki women who have fought for social justice for our people.”

Through her parents and extended family, Dana’s childhood was steeped in the language and culture of the Penobscot tribe. Today she lives with her young daughters on Indian Island where she was raised. Her mother Julia is the long-time teacher at Indian Island School; her father Barry ’84 was Penobscot tribal chief from 2000-2004.

Serving as ambassador to the Penobscot Nation can be both exhilarating and daunting. Dana draws on her spiritual connection with the land and water to sustain her. “I feel so fortunate to live on Indian Island. This community nourishes me,” she says. “When I walk in the forest and sit by the river, I can feel my ancestors with me.”

Grounded in her culture and guided by her own quiet courage, Maulian Dana hopes to help make the future brighter, not only for her daughters, but for all the children of the Penobscot Nation.

“Social change isn’t easy, but this is a marathon, not a sprint,” she says.

An earlier version of this story appeared December 27, 2017 in Maine Women Magazine. Updated and reprinted with permission.

“Courageous Citizenship”

In recent years Maulian Dana has received considerable attention in Maine and beyond because of her advocacy for Native American concerns. As is often the case with issues involving political and cultural disagreements, her efforts have received both praise and criticism.

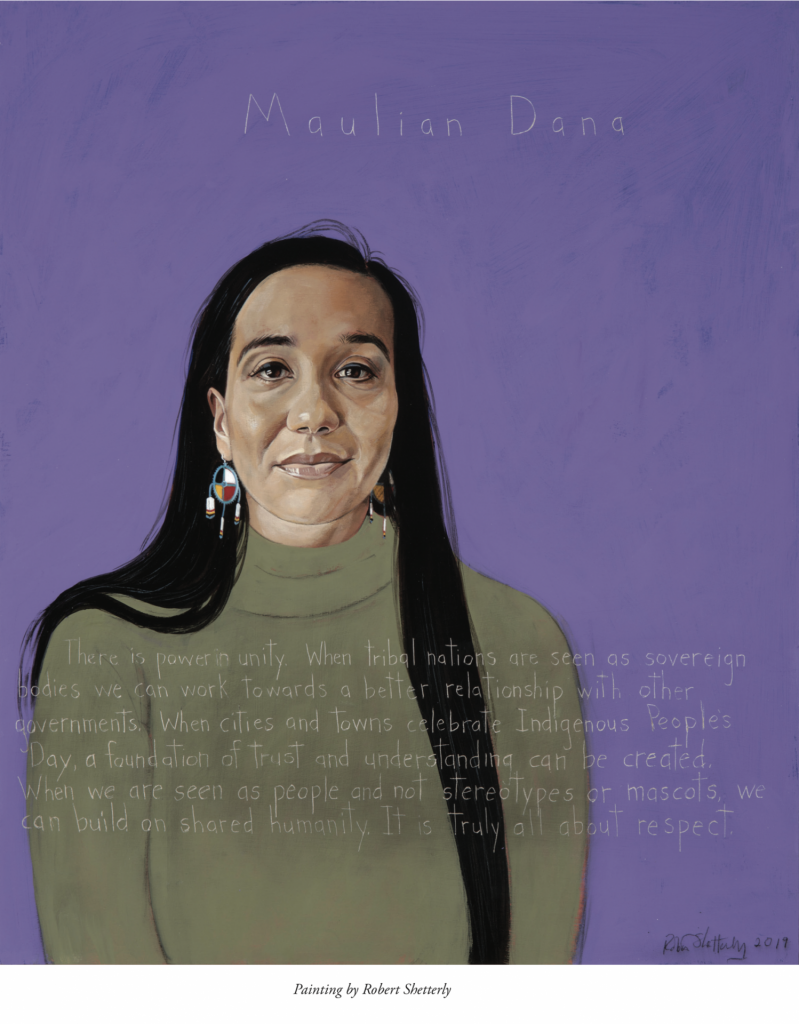

One noteworthy recognition came in 2019, when Maine-based author and artist Robert Shetterly featured Dana as part of his nationally prominent portrait series, “Americans Who Tell the Truth.” For nearly 20 years Shetterly has been painting portraits of Americans, both historical and contemporary, who, as “models of courageous citizenship,” have used their voices to address social and economic injustice and political and environmental threats.

As with all portraits in the series, Dana’s portrait features a quote of hers, etched into the image of the wood-panel painting, that reflects her cause and point of view.

There is power in unity. When tribal nations are seen as sovereign bodies we can work together toward a better relationship with other governments. When cities and towns celebrate Indigenous People’s Day, a foundation of trust and understanding can be created. When we are seen as people and not stereotypes or mascots, we can build on shared humanity. It is truly all about respect.

Dana’s 30” x 36” portrait is one of nearly 250 paintings Shetterly has completed for his series, elements

of which are included in traveling exhibits at museums and colleges throughout the U.S. More about

the portrait series may be found at: www.AmericansWhoTellTheTruth.org.