THERE ARE CERTAIN ALUMNI whose names are widely recognized by Black Bears of all generations. Stephen and Tabitha King. Bernard Lown. Cindy Blodgett. Raymond Fogler. Olympia Snowe.

Chuck Peddle’s name may not be among the most recognizable of UMaine alumni. But it deserves to be.

Before you could stream movies or access your bank account on your phone, before Google or Amazon or i-everything, even before Bill Gates or Apple’s two Steves (Jobs and Wozniak) there was Chuck Peddle, a 1959 University of Maine graduate whose innovation and leadership made those activities, companies, and careers possible.

Peddle led the development of a revolutionary microprocessor known within the technology industry as “the 6502.” For a computer, a microprocessor is its electronic brain. The development of the 6502 made consumer-affordable personal computers possible — and changed the world.

“More than any other person, Chuck Peddle deserves to be called the founder of the personal computer industry,” wrote veteran technology journalist Phil Lemmons in the November 1982 issue of BYTE magazine. Lemmons, who went on to become editorial director of PC World Communications, Inc., said, “Peddle made the personal computer possible.”

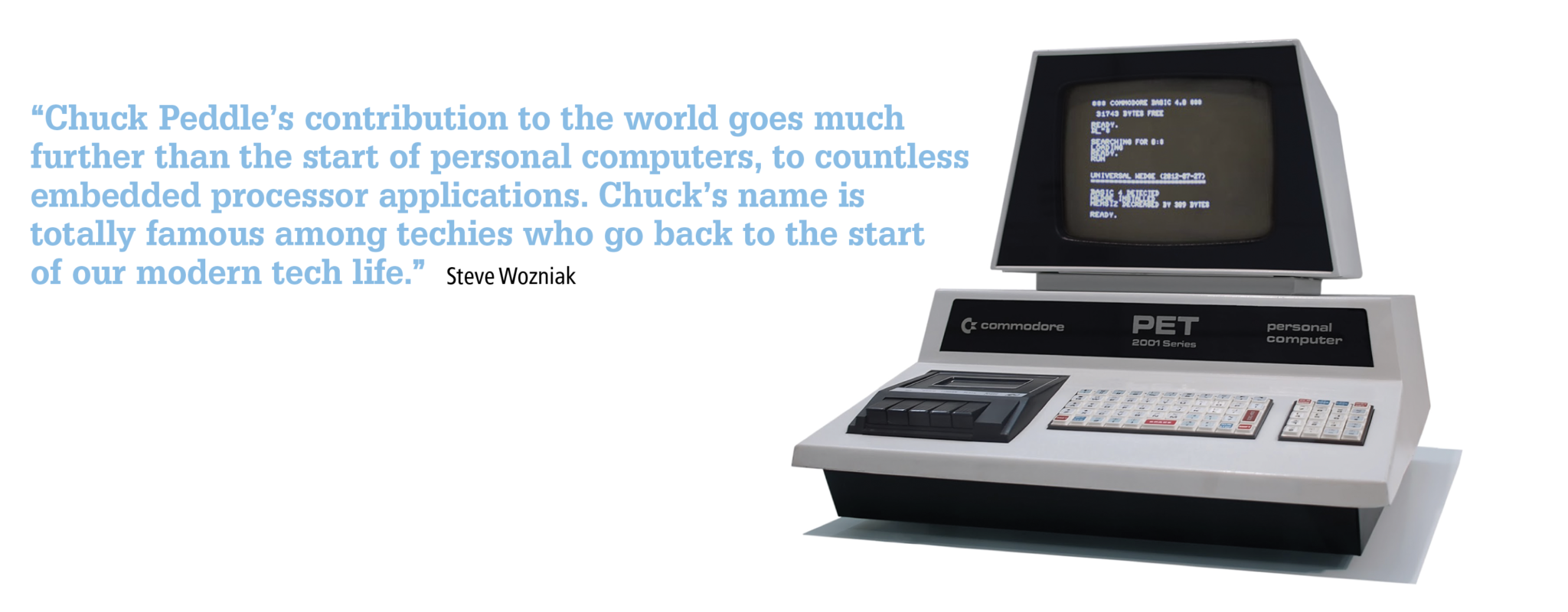

“Chuck Peddle’s contribution to the world goes much further than the start of personal computers, to countless embedded processor applications,” Apple co-founder Steve Wozniak told MAINE Alumni Magazine after learning that Peddle had been selected for UMaine’s 2019 Alumni Career Achievement Award. “Chuck’s name is totally famous among techies who go back to the start of our modern tech life.”

“Throughout his career, Chuck has been consistently ahead of the curve,” says Dana N. Humphrey, dean of UMaine’s College of Engineering. “Chuck may be known for his engineering prowess but he is also an industry visionary.”

Humphrey cites a handful of examples: Peddle’s role as “the driving force” behind the implementation of hard drives within personal computers. The now-ubiquitous gas pump credit card reader. And perhaps most notably, the development of “the 6502,” the microchip that made possible the world’s first personal computer, the Commodore PET, intentionally named to comfort tech-shy purchasers.

The Making of an Engineer

It’s a wonder at all that Chuck Peddle became an engineer, much less the father of personal computing. Growing up in a working-class family in Augusta, he says he never intended to go to college.

“I never planned on doing anything; we were just trying to survive because we were so broke,” he says.

The Monday following his high school graduation from Cony High School in 1955, his mother provided the first spark of motivation: She told young Charles to get out of bed and get a job. The employment office set him up with a road gang, swinging pick-axes and slinging shovels. He was no stranger to hard work; he had worked in mills, like his friends and others in his family. But there was a man on the crew who had worked his whole life laying down asphalt, who said the thing he most looked forward to in the world was when his landlady bought a quart of beer for him on Saturday so he could drink it on Sunday.

“This is bullshit,” he thought. “I want to do something with my life!”

So Peddle enrolled at UMaine, with a little help from then-President Arthur Hauck, who was aware of Peddle’s potential and arranged for him to receive a modest scholarship. Peddle studied engineering and made good grades. Still, as he entered his junior year, he says he still didn’t have a clue about what to do with his education.

One Class set him on Course

An engineer had joined the UMaine faculty from Massachusetts Institute of Technology (MIT), where he had worked with Claude Shannon, the legendary mathematician who introduced information theory to the world. Among many other breakthroughs, Shannon had demonstrated that Boolean algebra — the use of 1s and 0s — could translate into language. Peddle signed up for the new faculty member’s class on computer systems engineering.

“We studied the eye for four weeks, then we studied the ear for two weeks,” Peddle says. “He told us, ‘You can’t communicate with a human being until you know how they communicate.’”

Then, Peddle says, “He wrote down Boolean arithmetic. It was the first time I’d seen it. I was totally impressed. Then we started fooling with it, and I realized that what he was teaching me (was computer language).

“I was convinced computers were the future. I knew I wanted to do computers for the rest of my life.”

After a stint in the Marine Corps, Peddle went to work with General Electric, earning recognition as a world-class engineer during his 11 years with the company. He then joined Motorola and led the design of an early microprocessor, Motorola’s 6800. The technology was sound, but his potential customers — other tech companies — felt its $250 price tag was not cost effective.

Peddle relayed the feedback to Motorola with a plan to make a more affordable version of the 6800. The timing coincided with bits of information he had picked up from clients about a project being worked on by Intel: development of a new generation of semiconductors, a necessary component of microprocessors that Peddle thought could revolutionize computing and make microprocessors less expensive to produce and cheaper for customers.

But his bosses at Motorola weren’t interested in making a cheaper device. Deeply discouraged, Peddle and a team of engineers went to work for another company in the microprocessor business, MOS Technologies. Within six months, they had created the 6502 with a consumer price of $25 — one-tenth the cost of the Motorola 6800. Soon after that, MOS Technologies — and, importantly, its Peddle-led engineering team — was purchased by Commodore Business Machines, a move that would soon make the company the global leader in personal computing.

Ground-breaking, History-making

In the early 1970s, two very different markets for computers existed — one for corporations that squeezed the expansive machines into specially air-conditioned rooms; and another for hobbyists, the do-it-yourselfers who hooked up circuit boards in their basement or garage to see what they could make happen.

Peddle was one of the few techies who understood that with the right features, price point, and marketing, personal computers would become a high-demand consumer product.

“Nobody believed us. Everybody thought we were crazy,” Peddle said recently from his home in Santa Cruz, California. “We took an idea and created an industry — a big industry.”

Realizing Peddle’s vision for consumer-oriented personal computers required something that did not exist: an affordable, scalable microprocessor whose integrated circuitry could accomplish very complex activity. By 1975, Peddle and Commodore had come up with an answer: the 6502. Over the summer, they peppered trade publications with ads: In September, computer makers could buy their own 6502 for $25 at WesCon, an electronics show and convention in San Francisco.

Realizing Peddle’s vision for consumer-oriented personal computers required something that did not exist: an affordable, scalable microprocessor whose integrated circuitry could accomplish very complex activity. By 1975, Peddle and Commodore had come up with an answer: the 6502. Over the summer, they peppered trade publications with ads: In September, computer makers could buy their own 6502 for $25 at WesCon, an electronics show and convention in San Francisco.

The opportunity to buy Peddle’s cutting-edge processor attracted the attention of Apple co-founders Wozniak and Steve Jobs as well as many other members of the now-legendary Homebrew Computer Club, a group of techies who were instrumental in the eventual creation of the Silicon Valley technology complex in northern California.

“The Intel chip cost close to $400 (then) in single quantities,” Apple co-founder Wozniak told MAINE Alumni Magazine. “Chuck’s marketing plan for the 6501/6502 processors was to offer them directly for $20 and $25 at WesCon in San Francisco. This was unheard-of marketing but those of us who were ready to start a revolution wouldn’t miss this chance.”

For Peddle, there was a last-minute glitch. Event organizers wouldn’t allow companies to sell items on the floor of the show. Ever the engineer, Peddle quickly created a work-around. He rented a suite at the nearby St. Francis Hotel, and directed customers there.

“I went to WesCon and I remember paying $20 in cash for the 6501 processor, not knowing what its architecture and features were,” Wozniak recalled. “I also paid $25 for a 6502, which was the same to me but with one great simplification. I also paid $5 for a manual.

“I paid this [in] cash directly to Chuck and his wife,” Wozniak added. “Many of us in the Homebrew Computer Club bought our first microprocessor chips from Chuck.”

Al Alcorn, the man who invented Pong, the very first video game, remembers seeing Peddle in San Francisco. “Steve Jobs was there, we were there, MOS was there with a barrel full of 6502 processors. It became obvious how important that processor was going to be to launch the personal computer industry. It turned semiconductors into an electronics industry.”

The Rise of Commodore

All — yes, all — of the first successful home computing and gaming systems depended on the 6502. Peddle’s microprocessor also drove the most successful personal computers of the 1970s and early 1980s: the Commodore PET, which debuted in 1977; the Commodore VIC, launched in 1980; and the Commodore 64, which hit the market in 1982 and remains the best-selling computer of all time.

“The PET is big news,” Personal Computing magazine reported in 1977. It described Peddle’s PET as “a clean break from commercial and hobbyist computer systems … into a consumer market.”

In that article, Peddle presented his vision for how personal computers would affect lives. He posited that personal computers would one day connect with and access information from other personal computers. (Keep in mind: He said this 13 years before the World Wide Web would become a thing.) He spoke about home-based education and self-help resources that could be accessed through computer applications; using computer games to teach computing skills at an early age; and the inevitability of computer-assisted remote shopping, bill-paying, and banking.

Even the way people watch TV programs would change as personal computers became commonplace, Peddle told the interviewer in 1977.

The Personal Computing article assessed Peddle’s prognostications and the Commodore PET’s appeal with cautious admiration. “This is an experiment on a grand scale,” the story declared. “It remains to be seen if the market [Peddle] predicted really exists or is imaginary.” (Spoiler alert: Those market predictions proved real.)

Peddle later designed the VIC 20 and then the Commodore 64. The company was selling 22 million computers a year, far outpacing its competitors, and Peddle’s team won “computer of the year” for the PET and the C-64.

What made all of that possible, Peddle says, was simply the supply-and-demand principles of economics. Making computers affordable was perhaps the single most significant success that ushered in personal computing.

Eventually, his success at Commodore came at odds with Jack Tramiel, the company’s hard-charging founder and president. Peddle was the young engineer getting all the attention, which, he suspects, rubbed the image-sensitive Tramiel the wrong way. The parting was not amicable, and Peddle later lost his Commodore stock in legal proceedings.

Still at Work

At 82 years of age, Peddle hasn’t stopped. Along with his longtime partner Kathleen Schaeffer, he shuttles between homes in northern California and Sri Lanka. He’s currently working on a new computer built around Flash memory that, he says, he can build 25 percent cheaper than competitors.

“This time I’m going to make money,” Peddle jokes.

The future for engineers, Peddle says, is combining robotics with the biomedical industry. He advises other tech innovators to follow the approach that helped him succeed: Look for ways to drive an industry by repurposing available technology. But even more important than technical skills, he says, is the same thing that set him apart from other engineers — having big ideas and the determination to pursue them.

“You take a dream, and you build a dream, and you keep building on it and you don’t let anybody stop you.” ![]()

BASIC Negotiating

A seminal moment in the history of the Commodore PET occurred in a second-story office above a bank in Albuquerque, New Mexico, where a young technology entrepreneur named Bill Gates had set up shop.

A seminal moment in the history of the Commodore PET occurred in a second-story office above a bank in Albuquerque, New Mexico, where a young technology entrepreneur named Bill Gates had set up shop.

Gates had created something called Microsoft BASIC, a very user-friendly and versatile version of the most common programming language that computers use to perform functions. Chuck Peddle wanted the PET to run a custom version of BASIC that would optimize PET’s processing.

Demonstrating impressive business savvy, Peddle negotiated with Gates on a deal that has since become a noted reference point in the story of Gates’s career: a one-time, perpetual-use licensing fee of BASIC that practically gave away his product. In time Gates would readily acknowledge it was probably the worst deal he ever made.

Still, Gates and Peddle remained on good terms. Speaking at the 2006 Consumer Electronics Show in Las Vegas, Peddle offered what quickly became a much-cited assessment of technology’s two biggest figures at the time.

“There is nothing nice about Steve Jobs,” Peddle said, “and nothing evil about Bill Gates. Gates is a good man.”