By measures of time and distance, Jim Montgomery ’93 is well beyond his Alfond Arena glory days. His final hockey game for the Black Bears, during which his icon status was cemented with three consecutive third period goals, all assisted by future Hockey Hall of Famer Paul Kariya ’96, to lift the Black Bears to a come-from-behind 4-3 victory over Lake Superior State in the 1992–93 national championship game, occurred nearly three full decades ago. Yes, the legendary 42-1-2 season, ever vivid in UMaine fans’ minds, really did happen that long ago.

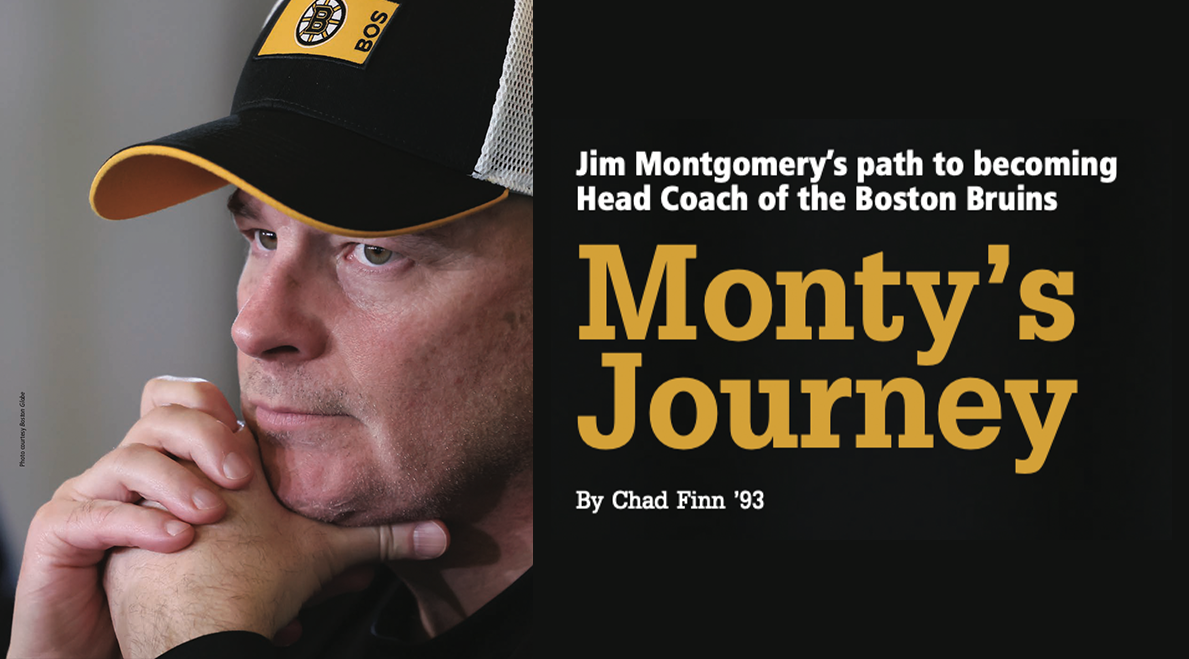

Montgomery’s hockey journey since, which included 12 seasons as a professional player and 19 now as a coach, presently has him situated 240 or so miles south of Alfond Arena, where he is in his first season as head coach of the Boston Bruins. He replaced a popular coach in Bruce Cassidy, who was unexpectedly fired in June 2022 after six seasons. The 53-year-old Montgomery quickly won over the Bruins faithful when the team rocketed out to a fast start, and remained the best team in the NHL at mid-season.

The Bruins, like a grander-scale version of the Black Bears in their heyday, are not so much a hockey team as a civic institution. Should Montgomery ever require a reminder of this, all he has to do is peek at his phone, where a long-running text thread with several Black Bear teammates reminds him of where he’s from, how far he has come, and the magnitude of being head coach of the Bruins.

“We have a thread where we shoot texts maybe two or three times a week,” said Montgomery during a November conversation in his office at TD Garden. “It’s most of our senior class.” He rattles off the names that are part of the thread, a who’s who of the best years of the UMaine hockey program. “There’s Snowy [Garth Snow ’93, ’94G], Eric Fenton ’93, Matt Martin ’94, Cal [Ingraham ’94], Kent Salfi ’93, Dan Murphy ’93, Justin Tomberlin ’01, Chuck Texeira ’00. And let me tell you, every once in a while, someone will say, ‘Dude, you coach the B’s. How amazing is that?’ It’s flattering, because it’s a reminder of how much the Bruins mean to people, especially here in Massachusetts. When I sit back, I have to remember that, how lucky I am, and be grateful for the opportunity I have.”

Those who watched Montgomery the most at UMaine understandably tended to see him in the present tense, as a scoring machine (his 301 career points remain a school record) and a natural leader whose fluency in French (he grew up in Montreal) allowed him to connect with every teammate. “Looking at it backwards now you can say, ‘Yeah, sure, it would not have been inconceivable in 1993 to see this future for him,’’ said Joe Carr, who as the team’s play-by-play voice broadcasted every game of Montgomery’s four-year career. Matt Bourque, UMaine’s sports information director at the time, perceived Montgomery much the same way. “If you ask me if I saw him as a future coach then, I should have looking back on it,’’ said Bourque, now an assistant commissioner of America East. “I don’t know if I’ve ever seen a better leader. He had a real big-brother, little-brother relationship with Paul [Kariya], who obviously was destined for greatness, but it didn’t matter to Jimmy whether you were a first-line player or a fourth-line player or a defenseman or a goalie, whether you came from Western Canada or a prep school in the Boston area. He just connected with everybody.”

It might come as a surprise to those who knew him then that even when Montgomery’s primary duty was to torment Hockey East goaltenders, he was already preparing for a coaching career. “I was thinking about it that far back,’’ said Montgomery. “Once I got around Shawn and Grant and how these guys had impacted my life, and the fun it looks like they have doing what they do, I thought, ‘That’s what I would love to do someday.’”

Shawn and Grant are, of course, the impossibly charismatic former head coach and program architect Shawn Walsh, and his top assistant and recruiter, Grant Standbrook. They worked so well together in part because they were so different — Walsh, who died at age 46 from cancer in 2001, often ran hot, while Standbrook was an understated master of precision. “But what they had in common was that they never stopped teaching,’’ said Montgomery, who still checks in with Standbrook, now retired and living in Naples, Florida, weekly. “Shawn always found different ways to motivate the team and/or individuals. And Grant was relentless in the pursuit of perfection, trying to get players to be the best they could be. There was so much to take away from being around both of them.”

Montgomery’s relationship with Walsh was symbiotic. The coach benefited greatly from having a leader of Montgomery’s capability in the locker room, and Walsh’s actions suggest he appreciated it. “Shawn obviously was a great coach and a great motivator,’’ said Bourque, “but I don’t think he was the easiest guy to play for. I think Jimmy did so much behind the scenes to know, ‘hey, maybe this guy needs a little bit of a pick-me-up, and this guy needs a little bit of a kick in the pants.’ I just think he was great that way. He really was.”

Part of the lore of the comeback in the ’93 championship game is a speech Montgomery made between the second and third period, the specific contents of which remain privy and almost sacrosanct to those who were in the locker room at the time. But Bourque recalls that Walsh’s faith in Montgomery as a motivator was made clear before the Black Bears’ first game of that Frozen Four, against the University of Michigan in the semifinals.

“I’ll never forget, we were sitting with [ESPN broadcasters] Tom Mees and Bob Norton the day before the Michigan game, and Bob asks a great question. ‘You’ve been [to the Frozen Four] before, you haven’t gotten to the championship game, what are you going to tell the team in the locker room before the game?’ And Shawn said, ‘I’m going to write our five team commandments on the board — Moses had 10 commandments, we don’t need that many, we’ve got five commandments — and then I’m going to turn the locker room over to Jimmy.’

“And I’m like, there’s no way he’s doing that. Shawn could tell a story or stretch the truth obviously. But it’s my understanding that he did that. That he went over short shifts and short passes and stay disciplined, and whatever the five commandments were, and then said, ‘Jim, it’s your room.’ He had that much trust in him, which was earned over that time. And obviously it was rewarded.”

Montgomery is on the opposite side of that coach/player dynamic now, but in a neat bit of symmetry, he’s benefiting from having outstanding leadership in the Bruins’ locker room much in the way Walsh did when Montgomery was his captain all those years ago. “The first time I talked with him after he had been here for a few weeks,” said Bob Beers ’90, a former UMaine defenseman — his final season was 1988-89, the year before Montgomery arrived — and the Bruins current radio color analyst. ‘’He said, ‘Beersy, I cannot believe the leadership in this locker room. It’s just fantastic, and that’s not hyperbole. These guys are so dedicated and accountable.’”

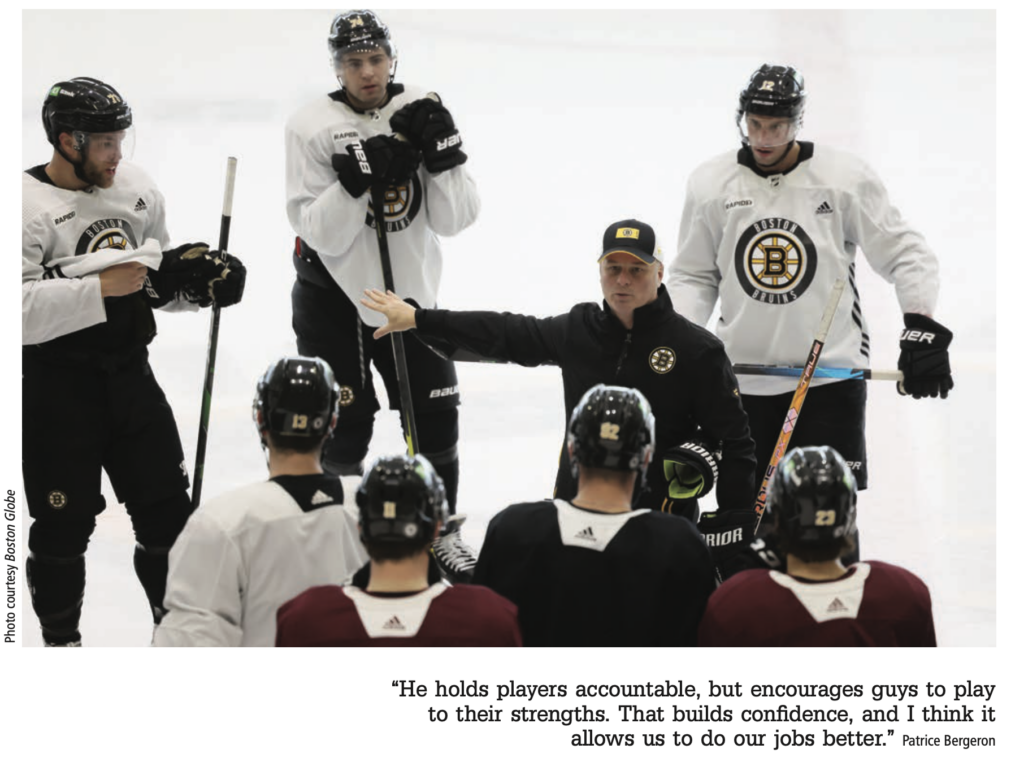

Three Bruins remain from the club’s 2010-11 Stanley Cup champion — forwards Patrice Bergeron, Brad Marchand, and David Krejci, who returned this year after spending last season in his native Czech Republic. All are consummate professionals, as are younger stars David Pastrnak and Charlie McAvoy. Bergeron, the classy captain who has been a Bruin since 2003, is the tone-setter for team culture, and said one of the reasons Montgomery got buy-in from the Bruins’ veterans right away is because of his straightforward communication skills. “He holds players accountable, but encourages guys to play to their strengths,’’ said Bergeron. “That builds confidence, and I think it allows us to do our jobs better.”

Montgomery said core tenets of his approach to coaching are “having the self-awareness to know what is working and what isn’t, being consistent in my message to the players, and always bringing everything back to what’s best for the team. If a coach thinks something is best for the team, he’s explained why, and if players don’t like it, at least they understand why you’re doing it.”

Beers says Montgomery has an almost innate ability to identify the ideal way to communicate with each individual player in a way that maximizes that player’s contributions. “He’s especially good at communicating necessary criticism,’’ said Beers. “Are you ripping guys when they come back to the bench after a shift, or do you sit down and talk with them post-game, watch some positive video and some negative video, and demonstrate in a constructive way what needs to be better? He does the latter, and it also helps that he’s upbeat, funny, and comfortable in his own skin.’’ Beers pauses. “Maybe he’s so aware of what other people are feeling because he’s been through a lot himself.”

The Bruins are not Montgomery’s first NHL head coaching gig. In May 2018, the Dallas Stars hired him away from the University of  Denver, where he had won a national championship and reached a pair of Frozen Fours in his five seasons as head coach. Montgomery was an immediate success in Dallas, guiding the Stars to the second round of the playoffs in 2018-19. But he was abruptly fired 31 games into his second season in December 2019 for what was termed “unprofessional conduct.” Montgomery received treatment and therapy for alcoholism, and says now that the Stars’ decision saved him. “Obviously, I had my own shortcomings as a person,” he says now, bringing up the subject without prompting. “I had to address that. I’ve become a better person, because I didn’t realize what the bottle was doing to me, but now I do.”

Denver, where he had won a national championship and reached a pair of Frozen Fours in his five seasons as head coach. Montgomery was an immediate success in Dallas, guiding the Stars to the second round of the playoffs in 2018-19. But he was abruptly fired 31 games into his second season in December 2019 for what was termed “unprofessional conduct.” Montgomery received treatment and therapy for alcoholism, and says now that the Stars’ decision saved him. “Obviously, I had my own shortcomings as a person,” he says now, bringing up the subject without prompting. “I had to address that. I’ve become a better person, because I didn’t realize what the bottle was doing to me, but now I do.”

Before hitting his self-inflicted crossroads in Dallas, Montgomery’s coaching path guided him to one success after another. Upon retiring as a player after a dozen years, with 122 games over six seasons spent in the NHL, he joined Jeff Jackson’s staff as a volunteer assistant in 2005-06 based in part on a past recommendation from Walsh. “We had lost Shawn by the time I was done playing,’’ said Montgomery, “but Jeff remembered his recommendation.” It was something of a gracious hire considering Jackson was the Lake Superior State coach in ’93 when Montgomery pulled off his hat-trick heroics in the title game. “I reminded him of it on occasion,” Montgomery said with a laugh. “One time I asked him to autograph a hockey card. It was me scoring my third goal.”

Montgomery moved from Notre Dame the following season to an assistant job at Rensselaer Polytechnic Institute in Troy, New York, where he shared an office with current UMaine coach Ben Barr, then a volunteer assistant just beginning his coaching career. “He is such a genuine person, and doesn’t change who he is, and that goes a long way in the hockey world,’’ said Barr, who was hired at UMaine by a search committee that included Montgomery, and remains a good friend. “It was no different with me. I was a 23-year-old kid trying to get into coaching, and he was a guy that played at the highest level, and he treated me the same way he would probably treat someone like Bergeron now.”

After four years at RPI and three as head coach with the Dubuque Saints of the US Junior Hockey League, Montgomery landed the University of Denver job in 2013-14. The Pioneers won the national title three seasons later, and the impressed Stars came calling after the 2017-18 season. “I wasn’t sure I wanted to go,’’ said Montgomery. “But it got to the point after my fifth year at Denver where if I didn’t go and I didn’t pursue it then the opportunities would probably stop coming.”

After that early success and sudden fall with the Stars, he found rejuvenation in St. Louis, where he spent two years on Craig Berube’s staff. “That growth there I can compare to the growth I got when I was a head coach in Dubuque for the first time,’’ said Montgomery. “Sitting back, learning the league better, watching a really good head coach, and then after last year, my second year there, I was like, ‘I’m ready to be a head coach again.’ I can’t tell you how grateful I am that the Bruins gave me that opportunity.”

No one gave him any such thing, of course. Montgomery earned it, by mastering the tactics and interpersonal complexities of hockey back during his days at Maine, and by taking accountability for his mistakes. The Bruins are fortunate to have him. But in the unlikely case that someday he needs a reminder that he’s fortunate to have them, well, that long-running text thread with his old buddies from Orono is just a glance at his phone away. M