THE GHOSTS OF Walter Crockett are at peace now, finally at rest as memories in the lives of his children.

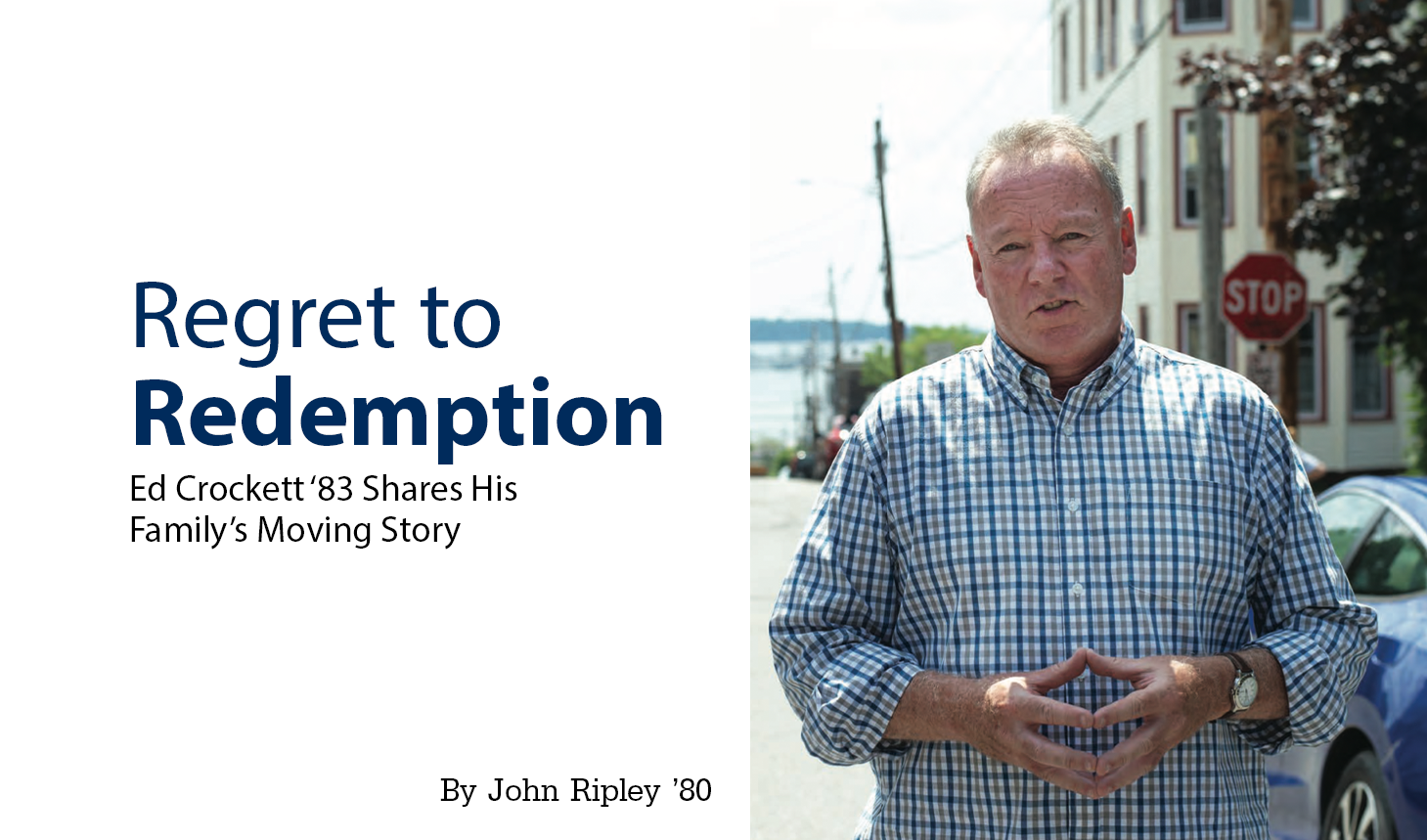

For one of his sons, W. Ed Crockett ’83, that armistice was forged from decades of heartache and embarrassment because of his father, and came only after acceptance, forgiveness, and a memoir, The Ghosts of Walter Crockett (Islandport Press, 2021).

Today, Ed Crockett is an accomplished runner, businessman, father, and member of the Maine House of Representatives. Like his father’s path in life, Crockett’s success was never assured, and was challenged by a complicated childhood on the hardscrabble streets of 1970s Munjoy Hill in Portland.

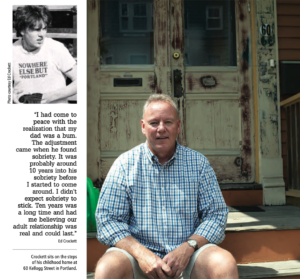

Both stories begin in a classic New England house at 60 Kellogg Street in the East End of Portland, a block over from where a Crockett relative, director John (Feeney) Ford, grew up.

Truthfully, however, Ed’s father, Walter, didn’t spend much time at 60 Kellogg; when he did appear, the reception was decidedly unwelcome. For decades, Walter spent his days and nights on the streets of Portland, panhandling, drinking, sleeping in alleys, fighting. His reputation was such that, when he died, his obituary in the Portland Press Herald referred to him as “the biggest drunk in Portland.”

Truthfully, however, Ed’s father, Walter, didn’t spend much time at 60 Kellogg; when he did appear, the reception was decidedly unwelcome. For decades, Walter spent his days and nights on the streets of Portland, panhandling, drinking, sleeping in alleys, fighting. His reputation was such that, when he died, his obituary in the Portland Press Herald referred to him as “the biggest drunk in Portland.”

“Of course, I didn’t need to see it in print to know the truth,” Ed Crockett wrote in the book’s introduction. “I lived it. It haunted me my whole life.”

The Crockett story in many ways parallels those of millions of others — immigrants landing in waterfront cities like Portland, working blue-collar jobs, raising large, boisterous families, perhaps joining the military to escape, dutifully attending Mass at the Catholic Church. And like other ethnic neighborhoods across America, Munjoy Hill was condensed, packed, and personal, and where families of Irish, Italian, and Jewish immigrants all looked after one another.

“My home, schools, church, and even my first four jobs were within this physical foot- print,” Crockett wrote. “Coincidentally, it was my father’s domain as well.” Even when not around, Walter’s presence lurked, he wrote: “On too many mornings, I would spy him out of the corner of my eye, a deeply flawed and crumbled mess of a man passed out on a bench reeking of alcohol. My friends sometimes nudged me and said, ‘Hey, isn’t that your dad?’”

And yet, despite those moments of hating his father, of even trying to deny his very existence, Crockett also was counterbalanced by a sense of compassion. The overriding question, really, was: “Am I destined to be just like him?”

ED CROCKETT didn’t originally intend to publish his memoir. He wanted to privately chronicle the lives that intersected, both in conflict and in love. It was history, catharsis, and a way to explain to his children how he became who he is.

“I started with a screenplay centered on my father’s years on the streets to early sobriety,” he recalls, though the project evolved into a memoir. An author friend inquired about read- ing the manuscript, and then asked Crockett if he could share it with his publisher.

The book in many ways reads like a movie, and it’s easy to imagine the scenery, the characters, the struggles, the progressions. The photos are black and white: grainy, honest snapshots not unlike those any of us have in boxes in the attic. Crockett describes both Portland and its battles with Urban Renewal, and his father’s own enormous, heartbreaking struggles. Whatever reasons Walter had to get sober, he always found an excuse to drink.

progressions. The photos are black and white: grainy, honest snapshots not unlike those any of us have in boxes in the attic. Crockett describes both Portland and its battles with Urban Renewal, and his father’s own enormous, heartbreaking struggles. Whatever reasons Walter had to get sober, he always found an excuse to drink.

And so, this was the haze of Ed Crockett’s life as he made his way through childhood and high school, experimenting with this and that to avoid his father’s fate. But if Walter was looming on the outskirts, his mother, Virginia, was the foundation, raising eight children on her own (along with 13 cats and three dogs). “I suppose 60 Kellogg Street had some charm,” Crockett wrote. “But it was a calamity.”For much of the time, Crockett found solace at school and church. Shy and lack- ing in confidence, school provided him with opportunities to attend summer camp, to find after-school jobs, to participate in sports and, eventually, to meet girls. First at Cheverus and then at Portland High, he excelled academically and then literally discovered his stride with long-distance running.

Life went on, even with Walter there on the outskirts, passed out on a bench in a park, watching his children from afar. In their own ways, Crockett and his siblings scratched to find their way in life. “That was just a tough situation,” said his older brother Danny Crockett, now an English teacher in Falmouth.

By 1978, Walter was again at the bottom of a bottle as a priest again administered last rites. He had gone on another bender after another Red Sox collapse — not the first time for either party. This time, however, because of his stint in the Army, Walt was admitted to the Togus Veterans Medical Center. It was there he met Ann, a psychology intern, who would turn out to be his guardian angel.

IT WASN’T LONG after that Ed Crockett made his way to Orono to attend the University of Maine. Not only did it fit the family budget, it was far enough away from 60 Kellogg Street to give him some space to grow. These years also supplied the content for new chapters in their intertwining stories, changing the flavor of the plot from tragedy to redemption and growth.

“I think getting to UMaine was unique for him to see he had all of these possibilities,” Danny said. “Orono opened a lot of doors for him.”

“The beauty of going away to college was that nobody knew about my challenging childhood,” Crockett said. “I was on an equal play- ing field for the first time. It set me free.”

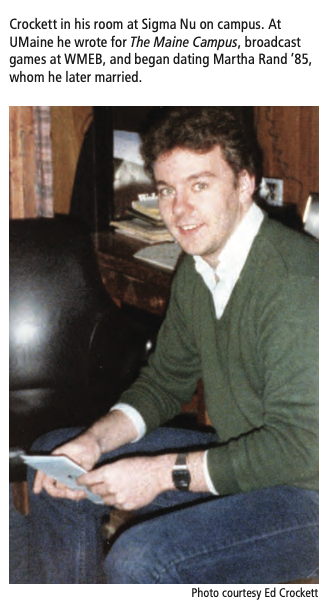

He dove headfirst into campus life, with its sports, academics, learning and working in journalism, the social gatherings — and the freedom from Walter. UMaine was a fresh start and where, arguably, he set a new course for his life.

“I grew up there. Probably the best thing I did was get involved. Writing at The Maine Campus as a freshman, broadcasting games at WMEB, working as the assistant sports information director, joining a fraternity, and most importantly meeting the love of my life, Martha.”

Part of that freedom, however, included testing the boundaries of his DNA: “I drank heavily four nights a week,” he wrote. And yet he was disciplined enough to tailor his social life with his academic and athletic goals. “The specter of my father was always in my head,” he said.

As it turned out, Walter, as well, was exploring new ground: he was not only sober, but engaged to Ann, his guardian angel.

For the Crockett children, there was, to be sure, skepticism.

“I guess the news about my father was a good thing, but I had no faith in him,” Crockett wrote. Despite the odds, and a brief relapse or two, Walter was sober. “Walter got better,” Danny said. “He got his life back together.”

“I guess the news about my father was a good thing, but I had no faith in him,” Crockett wrote. Despite the odds, and a brief relapse or two, Walter was sober. “Walter got better,” Danny said. “He got his life back together.”

During the ensuing years, Walter remained sober. There was an awkward meeting with Ed at the UMaine campus, and various attempts, some of them misfires, to reconcile.

But the truth was: somehow, improbably, impossibly, Walter Crockett was sober. And he would remain so for the rest of his life.

“It was probably around 10 years into his sobriety before I started to come around,” Crockett said.

IF THIS WERE a script as Crockett originally envisioned, we might fast-forward to a scene in October 2012. Walter is at Maine Medical Center, age 79, sober for 30 years. There’s a priest. Again. Walter passed shortly after, at peace, soon to be tagged with that ignominious label from his hometown newspaper — “the biggest drunk in Portland” — an entire book defined by a single chapter.

Ed Crockett forgave his father and continues to position his mother, Ginny, as the true foundation, the strength, of this story of struggle, failure, and redemption.

And as with happy endings, Crockett’s adulthood did not parallel his father’s. After UMaine he worked at WABI-TV in Bangor, attended graduate school, and then became a business executive for some of Maine’s most prestigious companies: Lepage Bakeries, Hannaford, Oakhurst Dairy and, for the last decade at Capt’n Eli’s Soda, where he now serves as president. And then, in 2018, he was elected to the Maine Legislature.

“Being entrusted with the responsibility of trying to help your neighbors is a great honor,” he said.

Crockett’s success, it can be said, ensured that the ghosts of Walter Crockett are, indeed, at rest.

“For Eddie,” said Danny, “Things came around to where he hoped they would be.” ![]()