By John Ripley ’90

How tragedy fueled Lynn Bolduc’s passion for organ donation

THE QUESTION MIGHT BE: how did an unspeakable teenage tragedy not ruin Lynn Henderson Bolduc’s life, robbing her of love, happiness, and the most  modest of futures? Or, perhaps it is: how did Bolduc ’90, ’02G go even further, converting her heartbreak into literally giving parts of herself to help others?

modest of futures? Or, perhaps it is: how did Bolduc ’90, ’02G go even further, converting her heartbreak into literally giving parts of herself to help others?

The answer to both is a story of love, guilt, redemption, and astonishing selflessness.

On any given day, there are 100,000 Americans waiting for a kidney donation. And, on any given day, more than a dozen of them will die, having waited for an unrealized miracle.

Bolduc’s path from what promised to be a normal life to an extraordinary one was an incredibly taxing journey — one that continues today.

At the age of 14, with the support of her parents, Bolduc ended a pregnancy that was the result of date rape. As she moved on with her life — attending college, finding a profession, and starting a family — Bolduc continued to be nagged by a sense of shame.

And then, in 2014, she saw a social media post about organ donation. She began to quietly investigate becoming a non-directed donor: donating to someone who isn’t related.

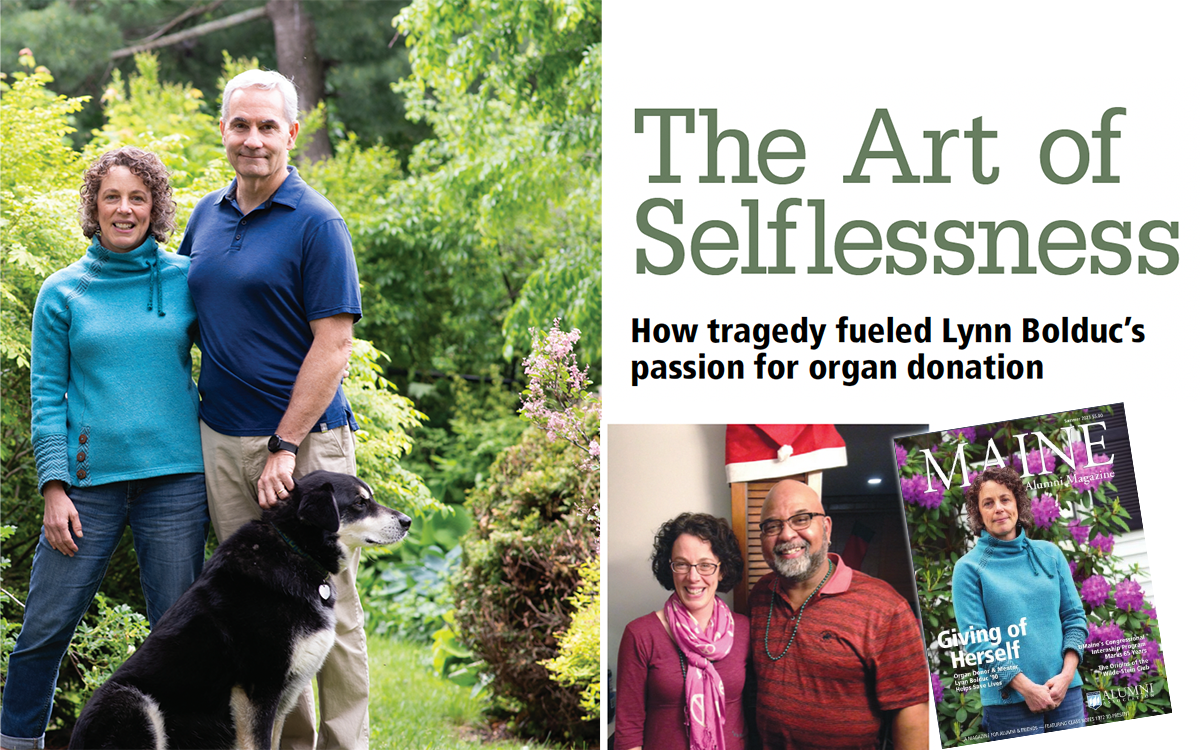

“So there was something compelling about this post that spoke to me because I wanted to do something right,” Bolduc explained on the podcast, Donor Diaries. “I think that a piece of me thought that in doing this thing I would somehow try to make things right for myself. I think in donating an organ I was trying to just pay back what I felt guilty about doing.” Bolduc called the number in the post, connecting to Brigham and Women’s Hospital in Boston. When she broke the news to her husband, Ray ’90, he was supportive, and the process moved rather quickly after that.

“When Lynn told me she wanted to donate her kidney, I questioned why she wanted to do this for a stranger, but after seeing how passionate she was about this donation, I felt more confident everything would be okay,” said Ray. “She had such a great experience with the kidney from the all-day testing, the surgery, and the recovery, this has made her a better person, which made everyone around her a better person.”

“When Lynn told me she wanted to donate her kidney, I questioned why she wanted to do this for a stranger, but after seeing how passionate she was about this donation, I felt more confident everything would be okay,” said Ray. “She had such a great experience with the kidney from the all-day testing, the surgery, and the recovery, this has made her a better person, which made everyone around her a better person.”

Sometime later, Bolduc received a letter from the recipient, Aaron Neely of the Cleve- land area: “I hope you will be pleased to know I take this gift very seriously,” he wrote. “I will not let your gift to me be in vain.”

In fact, Bolduc’s gift doubled immediately: as part of a program to accelerate the process for Aaron, his wife, Marie, also donated a kidney the very next day.

“It’s definitely harder to watch someone live on dialysis,” said Marie. “My husband is a very good man; the decision I made … there was no decision to make. I never had any hesitation.”

The Bolducs and the Neelys met in person on December 8, 2016, the second anniversary of the donation, and now reconnect each year. Aaron’s mother gave Bolduc a long hug. His granddaughters said she saved their “Papa.” “It made me feel uncomfortable; it is at times uncomfortable to be told you’re a hero, ‘you saved my life,’” Bolduc said. “Those are big words. I don’t really feel any different from most people.”

And so life continued on for the Bolducs and the Neelys, with Aaron back to an active lifestyle of gardening, kayaking, and other pursuits. “It’s our hope that he will die at an old age with Lynn’s kidney,” Marie said.

BOLDUC EVENTUALLY CHANGED professions. After graduating with degrees in nutrition, Bolduc spent most of her career as a dietitian in the surgical weight-loss field and for dialysis patients.

But her donation experience became even more of a passion and she began working for the National Kidney Donation Organization (NKDO), mentoring and educating potential kidney donors. Data, she said, indicate that of those who originally sign up to donate, only about one percent will go through with it; with mentoring, however, that figure more than triples.

Through her work as a mentor during the past year and a half, Bolduc has connected with more than 800 donor candidates, of whom more than 50 have become kidney donors, according to Terri Thede, the project manager for NKDO.

“So we need a heckuva lot more people in the United States like Lynn,” said Matt Cavanaugh, the NKDO President and CEO and himself, like Thede, a kidney donor.

Bolduc, however, still had more to give.

According to the NKDO, fewer than 200 living in the United States have donated both a kidney and a portion of their liver to two recipients. Bolduc is one of them.

According to the NKDO, fewer than 200 living in the United States have donated both a kidney and a portion of their liver to two recipients. Bolduc is one of them.

While at UMaine, Bolduc learned during an animal physiology class that the liver is the only solid organ that regrows. And so when the urge to help others began to gnaw at Bolduc a few years after donating her kidney, there was another social media post, another application, another hospital stay.

That day in March 2022 at the Lahey Hospital outside Boston, the Bolducs sat in the pre-surgery reception room. Pretty much everyone there had white hair, except for one: a young lady who they quickly realized was to be the recipient, sitting with her mother in a loveseat.

“She was very tiny, she was so tiny,” Lynn told Donor Diaries. “She might’ve been five feet tall, and she had her hair in pigtails.”

There were complications and the surgery lasted longer than expected, some 10 hours. The next day, the Bolducs learned that the 23-year-old recipient had died during the operation.

“My team was devastated. I was devastated,” Bolduc told Donor Diaries. “I can only imagine her mom. I spent most of my time in the hospital in tears.”

Sometime later, Bolduc found the young woman’s obituary, and planted a tree in the yard in her memory. Not unexpectedly, the emotional toll was the most difficult part of her recovery.

“Emotionally the recovery was tougher knowing I had not actually saved anyone with my liver donation and would have a longer physical recovery,” she said. “I had a couple of really good counseling sessions that helped me see that though I had not saved (the recipient), I gave her hope. That day she walked into the OR she was hopeful. It is something I cling to.”

For the Bolducs, hope is less of an emotion than a call to action; it’s what drives them both to sacrifice so much for others. This fall, in fact, Ray also will become a kidney donor.

“He is going to help a man in Massachusetts who needs a second kidney, and is about our age with children still in the house,” Lynn said. “What a gift.”

IN SPEAKING WITH the Bolducs and the other donors, there is definite interest in sharing the gospel of organ donation.For a kidney donor, the risk is relatively minor — it’s less dangerous thana Caesarean section — and patients are typically back to work within a few weeks of surgery. In addition, said NKDO’s Cavanaugh, while a kidney from a cadaver might last a dozen years, a donation from a living person could last 20 years or so.

And yet there’s a hesitancy, an “it’s-not-about-me” humility that runs through the storyline.

“That also is one of the things that makes it sometimes difficult for kidney donors to talk about their donation: they’re humble,” Cavanaugh said. “They don’t like talking about that.”

And yet, Cavanaugh notes, the effect that Bolduc has had on literally hundreds of lives cannot be denied. “Lynn is a life-saver,” he said. “She’s saving lives routinely.”